Reflecting on the international implications of President Donald Trump’s early policy decisions, the Wheeler Institute in collaboration with the Geopolitics and Business Club at London Business School, hosted an event on May 12 exploring “President Donald Trump’s First 100 Days: What Comes Next?”

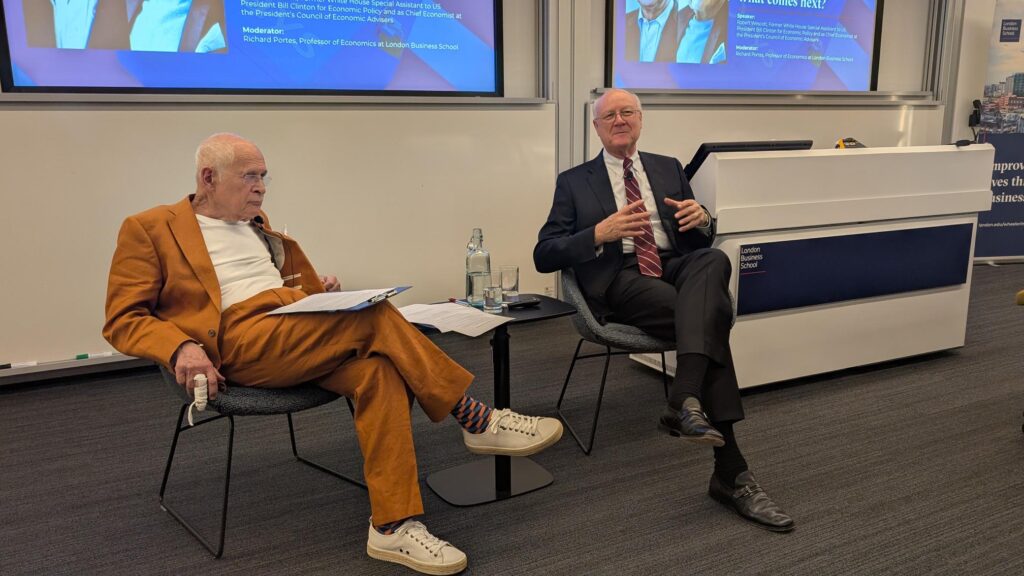

The session was hosted by Sergei Guriev, Dean of the London Business School. Featuring a conversation between Richard Portes, Professor of Economics at London Business School and Founder of the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and Robert Wescott, Founder and Senior Advisor of Keybridge Research in Washington, DC and former Special Assistant to the President for Economic Policy at the White House of President Bill Clinton.

American Economic Policy at a Crossroads: 100 Days into Trump’s New Presidency

The first 100 days of a presidency often set the tone for what is to come. In the case of President Trump’s return to office, these early days have been marked by large shifts in economic and social policy and by increases in uncertainty. While the President’s core supporters remain steadfast, there are concerns about public confidence and economic stability, and the President’s approval ratings have declined over his first 100 days.

A Tariff-Led Policy

Tariffs have been the centrepiece of President Trump’s economic strategy, echoing a nostalgic vision of America’s “golden era” between 1870 and 1913. During this period, the country charged relatively high tariffs, and the US rose to global economic dominance through industrialisation and the rise of manufacturing. This period also saw the ascendance of the American navy—the rise of the “Great White Fleet”—the conquests of the Philippines and Cuba, and the construction of the Panama Canal. However, this period also saw the distorting economic effects of tariffs, which many economists believe impeded the rise of the service sector in America. Later, high American Smoot-Hawley tariffs passed in 1930 brought retaliatory tariffs by 24 countries around the world within two years, contributed to a roughly two-thirds decline in the volume of global trade, and contributed to the Great Depression, illustrating the damaging consequences of protectionist policies.

Trump’s latest tariffs have been associated with a drop in consumer confidence and a sharp upswing in inflation expectations. In response, households have been bringing forward purchases, creating temporary spikes in motor vehicle and electronics sales ahead of expected price increases. At the same time, many businesses appear to be delaying capital expenditures due to policy uncertainty. This combination of falling consumer confidence and softening capital spending can be a precursor to recession.

A Waning of American Exceptionalism?

Over many decades, America has built up a great reservoir of soft power and has become attractive as a global investment destination. For years international investors have been committed to the US market due to its stable economic policies, innovation, strong science, university research, entrepreneurship, and supportive regulatory and tax structures. However, there have been rising concerns that some of these historical American strengths may be eroding.

American universities are facing reductions in research funding and potentially rising taxes on their endowments. At the same time, ongoing debates over immigration policies and resistance to diversity and inclusion initiatives have further contributed to uncertainty. These developments have raised concerns about a possible reverse brain drain—where highly-skilled researchers choose to return to or relocate to their home countries or other nations offering more favourable conditions for academic and professional growth.

As a result of these shifts, some large European institutional investors are now reassessing this so-called “American Exceptionalism” and are redeploying capital back to Europe.

Unravelling the Policy Process

Much of the administration’s policymaking process appears less formalised compared to previous administrations. Historically economic, political, and security issues have been carefully debated by expert advisors through White House National Security Council and National Economic Council policy processes and then presented to the president for ultimate approval. The current policy process at the White House has a clear “top down” structure, appears to rely on less analytical input, and often has an “on again, off again” nature where, for example, tariffs are imposed, delayed, reinstituted, etc.

This appears to be contributing to rising economic uncertainty. Although early indications suggested that tariffs would serve mainly as a negotiating tool, they have instead become a core part of the administration’s economic policy. Trade partners have responded in kind with retaliatory tariffs, and although efforts to reduce tariffs have made some progress, little remains resolved at this time. Meaningful trade negotiations are complex and often take years to negotiate. For example, the renegotiation of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), which became the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement during President Trump’s first term, took two years of intensive discussions, even though the countries already shared a well-established trade framework. This highlights how ambitious it is to expect comprehensive trade agreements with major economies like China to be concluded in a matter of months.

Meanwhile, the administration introduced the so-called DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) Program under the direction of businessman Elon Musk as a cost-cutting initiative aimed at reducing government spending. These policies have already had a significant impact on US institutions, particularly those dependent on federal funding like universities and research centres, but also on American foreign aid programs. As grants and public investments were scaled back, institutions have faced difficult budget decisions, leading to programme closures and staff reductions. The ripple effects appear to be extending beyond the public sector, undermining consumer confidence as layoffs increase and economic uncertainty grows.

Are We Looking at a Manufactured Recession?

Should the US economy slip into recession in the coming months, it is likely to be driven more by recent policy shifts, especially new tariffs, than by typical cyclical downturn drivers—such as an oil shock or a central bank tightening effort to combat rising inflation.

The warning signs are rising. Economic growth is slowing. Business investment is looking weaker and important industries, such as energy and sustainable infrastructure, are already scaling back projects amidst budget cutbacks and uncertainty. Even the oil and gas sector, traditionally a beneficiary of Republican deregulatory policy, seems to be moving sideways with its investment plans due to falling consumer confidence and worries about an economic downturn, which are bringing lower oil prices.

There is also evidence of financial instability. In the days following ‘Liberation Day’ (April 2, the administration’s tariff policy launch day) there was a sharp increase in bond yields and a subsequent depreciation of the US dollar. This was an unusual dynamic, as rising yields typically attract foreign investment and boost the value of the dollar. The decline in almost all US asset classes appears to have reflected a collective concern about the country’s economic management.

Although markets have since rebounded to pre-Liberation Day levels, this recovery may reflect short-term optimism rather than a fundamental improvement in economic conditions. Markets seem to be underestimating the potential risks of ongoing policy uncertainty, rising inflation expectations, and weakening consumer confidence.

Final Reflections: Can the Tide Be Turned?

Despite these challenges, the fundamental resilience of American institutions should not be underestimated. Periods of economic slowdown have historically prompted political and institutional adaptations.

Looking ahead, it remains to be seen whether American constitutional checks and balances will continue to play a strong role in shaping policy outcomes. For the Democratic Party, this moment may present an opportunity to redefine itself, potentially as a party that offers practical solutions to the day-to-day problems of US citizens, like building more housing, promoting more public infrastructure, and boosting more resilient manufacturing centres.

As the UK grapples with its own economic challenges, notably the NHS crisis and housing shortages, there are important lessons to be learned. Populist movements often gain traction when governments struggle to address the everyday concerns of their citizens. And history suggests that nostalgic economic policies, while attractive for a period of time, frequently fall short in addressing fundamental challenges.

Speakers

Robert F. Wescott is Founder and Senior Advisor at Keybridge Research, an economic research firm based in Washington, DC, that has served global financial institutions, Fortune 500 companies, leading nonprofits, and government agencies since 2001. Wescott served for four years at the White House of President Bill Clinton as Special Assistant to the President for Economic Policy and as chief economist at his Council of Economic Advisers. He also was Deputy Division Chief in the Research Department of the International Monetary Fund, where he helped prepare the Fund’s semi-annual World Economic Outlook. Earlier Wescott was the first research director at the International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development (ICSEAD) in Kitakyushu, Japan. Wescott holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Pennsylvania and has published research papers in the areas of macroeconomics, energy economics, fiscal policy, inflation, trade policy, global financial crises, and geopolitical risks.

Richard Portes, Professor of Economics at London Business School, is Founder and Honorary President of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and Co-Founder of Economic Policy. He is an elected Fellow of the Econometric Society and of the British Academy. He has been Chair of the European Systemic Risk Board Advisory Scientific Committee, of which he remains a member, and he is Co-Chair of the ESRB Joint Expert Group on Non-bank Financial Intermediation as well as of the new ESRB Crypto Assets Task Force. He is a founder member of the Bellagio Group on the International Economy and the Euro50 Group. He is an Academic Director of the AQR Asset Management Institute at LBS.

Professor Portes was a Rhodes Scholar, then an Official Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford (of which he is now an Honorary Fellow). He has also taught at Princeton and Birkbeck College (University of London). He was the inaugural holder of the Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa Chair at the European University Institute, and he has been Distinguished Global Visiting Professor at the Haas Business School, UC Berkeley, and Joel Stern Visiting Professor of International Finance at Columbia Business School. He holds three honorary doctorates. He has written extensively on sovereign borrowing and debt, European monetary issues, European financial markets, macroprudential regulation, and international capital flows. Professor Portes was decorated CBE in the 2003 New Year’s Honours.

Author

Gabriela Tomova (MIF 2025) is a Masters in Finance student at London Business School. Prior to the MiF, she completed her undergraduate studies in Economics at Erasmus University and worked at the London office of JPMorgan in product development with a focus on fintech and technology in capital markets. Gabriela is an intern for the Wheeler Institute, contributing to the creation of content that amplifies the role of business in improving lives.