When heavy rains once again pushed parts of Porto Alegre in Brazil underwater last year, it underscored a pattern across many emerging markets: climate shocks are arriving faster than cities can rebuild. For emerging economies, climate-related disasters can cost approximately 0.3% of GDP annually, yet nearly 70% of those economic losses remain uninsured [1]. Floods and heatwaves are becoming part of everyday economic risk. Against this backdrop, financing “resilience” rather than “recovery” has become increasingly urgent.

A Proof of Concept

In October 2025, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government issued the world’s first certified resilience bond under the Climate Bonds Initiative’s Resilience Taxonomy [2]. Weeks later, the Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean (CAF) issued USD 100 million in resilience bonds [3], marking one of the earliest applications of the instrument in an emerging market setting.

While Tokyo set the technical benchmark, CAF’s issuance is a critical test of whether resilience finance can thrive in emerging markets where climate exposure is high, data can be uneven, and public resources are often stretched.

The Mechanics: Resilience Bonds and What Lies Ahead

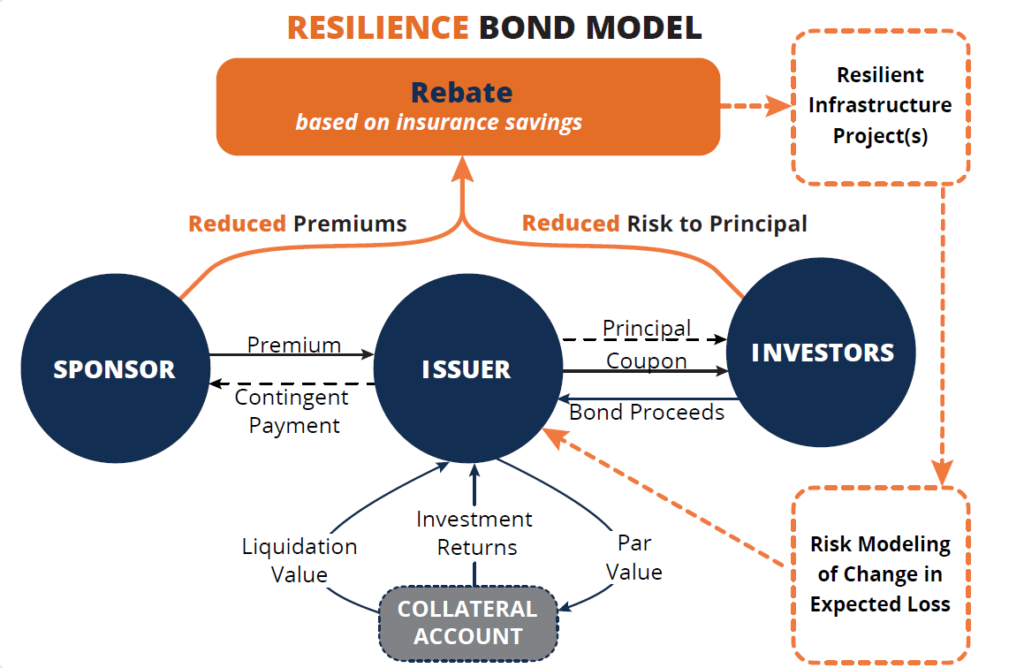

At its core, a resilience bond today resembles a traditional infrastructure bond: investors provide capital, and issuers use the proceeds for projects such as upgraded drainage systems, flood-resistant mobility corridors, or nature-based buffers. While current issuances like CAF’s focus on earmarking funds for certified resilience projects, they are paving the way for an innovative and integrated model that changes how risk reduction is valued.

Every resilience project lowers a portion of expected losses during extreme events. These avoided losses, such as fewer flooded homes, shorter transport outages, and reduced damage to utilities, can now be modelled with far greater accuracy. When insurers recognise lower expected claims due to better infrastructure, they can price that into lower premiums or structured rebates.

Source: OECD, Re:focus Partners (2017), Re.bound Program Report, p.6. [4]

For instance, think of it like a ‘no-claims bonus’ for a city. Traditionally, a city bears a massive financial burden to manage its disaster risk. In this new model, the city uses a bond to build a specific project, like a strategic sea wall. Because that wall makes a flood much less likely, it reduces the city’s overall cost of risk. The city then captures the resulting “savings”, whether through lower insurance premiums, structured rebates or re-priced coupons. Thus, effectively, helping them pay down the project costs.

Importantly, investors still earn a market-aligned coupon. The benefit flows to the issuer, not from investor sacrifice but from a fundamental re-pricing of risk as insurers acknowledge that well-built infrastructure significantly reduces future liability. This alignment works because all parties gain when expected losses fall.

Need for Resilience in Emerging Economies

Infrastructure in emerging markets is often more exposed and fragile. A few days of transport or power disruption can have outsized effects on small businesses and informal workers. This makes risk reduction financially significant: even modest upgrades can generate massive value in avoided losses.

CAF’s bond channels capital into water systems, sanitation, and climate-resilient mobility, the very systems that recent storms had overwhelmed. If improved drainage prevents multi-week disruptions like those seen in southern Brazil last year -the economic justification for resilience becomes clear.

Building Momentum and Potential Challenges

Three shifts are making resilience finance more viable today. First, with the advent of machine learning and computing capabilities, risk modelling tools have improved: cities can now estimate avoided losses despite imperfect data. Second, the economic cost of climate downtime is clearer to insurers and corporates, who increasingly view resilience as a cost-avoidance strategy. Third, there is investor demand for long-duration, climate-aligned assets. A resilience bond offers the stability of conventional infrastructure finance while directly addressing climate vulnerability.

The model still faces some limitations. Measuring avoided losses remains complex, and credibility depends on independent verification. The resilience-oriented project pipeline is thin; many infrastructure plans are not designed with resilience metrics in mind. Also, for rebates to work, insurance partnerships must be built on robust actuarial foundations. Having said this, early integration of risk assessments into infrastructure planning, better local data systems, and development banks acting as anchor issuers can strengthen this market.

A Path Forward

The shift from ‘rebuilding aftershocks’ to ‘preventing impacts’ would be transformative for many cities. By integrating risk assessments early and using development banks as anchor issuers, we can turn climate risk into investable protection. As we look toward the future of sustainable finance, resilience bonds offer a way to ensure that the next storm doesn’t wash away years of developmental progress.

About the writer

Shivam Jain is a MiF 2026 candidate at London Business School and a Research Intern at the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development. Before joining London Business School, he was an Investment Specialist at Mercer, where he advised pension funds and endowments on global asset allocation and investment strategy. Shivam is focused on how channelling capital through innovation and policy design generates investment opportunities for sustainable growth. He is particularly interested in how capital allocation and incentive drivers can be used to support long-term economic development in emerging markets.

Citations

[1] Tek, A. (2024, November 27). Climate change and emerging markets: The property protection gap challenge. PEAK Re https://www.peak-re.com/en/knowledge-hub-insights/climate-change-and-emerging-markets-the-property-protection-gap-challenge/

[2] Tokyo Metropolitan Government. (2025, October 27). Issued the world’s first resilience bond, “TOKYO Resilience Bond.” https://tokyo-resilience.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/en/news/3676/

[3] CAF – Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean. (2025, November 14). CAF issues first resilience bond for Latin America and the Caribbean with support from UNDRR. https://www.caf.com/en/currently/news/caf-issues-first-resilience-bond-for-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-with-support-from-undrr/

[4] OECD, Re:focus Partners (2017), Re.bound Program Report, p.6., https://www.refocuspartners.com/wp-content/uploads/pdf/RE.bound-Program-Report-September-2017.pdf

Student voice

The Wheeler Institute for Business and Development is seeking to understand, illuminate and offer solutions to the challenges faced by the developing world, with an aim to identify the role of business in addressing these challenges and a focus on the implications and actions for those in developing countries. In support of our students, we approach this blog section as a reflective platform and a space where individuals can generate debate as long-term agents of positive change. This article is solely authored by a student and reflects their individual research, opinion and point of view and is not based on research led or supported by the Wheeler Institute.