Attention on climate change and efforts to mitigate its impact has increased exponentially from investors and financial markets in the last decade. From a financial perspective, this focus has led to considerable investment towards climate change mitigation initiatives, such that the pressure is now on businesses that are not doing enough. As part of the Wheeler Institute Climate Initiative, Lucrezia Reichlin, London Business School Professor of Economics and trustee of the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation, hosted a webinar with Mr Frédéric Samama, Head of Strategic Development at Sustainability, S&P, titled “the new-challenge of being carbon neutral by 2050”.

Investor awareness about climate change following the 2009 Global Financial Crisis

When Mr Samama pivoted his focus to climate change mitigation in 2009, the financial markets were in complete disarray following the Global Financial Crisis. In many instances, due to the lack of funding available, existing efforts in relation to climate change suffered from lack of investment and funds being directed elsewhere to more “pressing needs” within companies. Given the severity of the GFC and the increasing urgency to address the climate crisis, Mr Samama was inspired to understand whether we have explored all options when it comes to the role of financial markets in solving the climate crisis and whether out-of-box solutions can be developed.

It’s interesting to note that, at this time, any efforts focused on climate change were solely in the hands of governments and NGOs. The notion of investors being involved in climate change efforts was entirely new. Mr Samama believed that this needed to change as there were other parties, such as sovereign wealth funds, which (despite harsh criticism from governing entities) were ideal candidates to engage on climate change efforts as they have considerable funds, limited liability, long-term investment horizons and inter-generational wealth transfer capabilities. In short, investors such as sovereign wealth funds were great candidates for involvement in climate change efforts as their long investment horizons enabled them to internalise negative externalities, take on risk and generate returns while positively impacting society.

With that in mind, Mr Samama and his team developed a 3-level strategy combining debate, conversation and action to boost climate change initiatives:

- First, he expanded the stakeholders involved to bring policy-makers, academics, practitioners and (most importantly) investors into the conversation

- Secondly, he facilitated debates among the newly-expanded stakeholder group to address pressing questions around how investors can fit, what is the value of long-term investing etc.

- Finally, he leveraged the output to develop some concrete solutions. And his efforts have had initial success – he has developed a dedicated low-carbon index, he has facilitated the establishment of the Network for Greening Financial system (more than 100 central banks are getting mobilized around climate change) and Climate Action 100 (500+ investors representing over $50T are engaging with top 100 most polluting companies), he has testified in front of the Senate, among other achievements.

Despite governments and investors coming together, a lack of transparent and scalable solutions presents incredible challenges for financial innovation

While previous efforts to bring multiple stakeholders into the fold have raised investor interest, there is still much work to be done. Notably, in developing clear, tangible and transparent solutions to move investor money towards mitigating climate change. At COP26, several public entities and private investors (including banks, insurance companies, asset owners, asset managers etc.) committed to becoming carbon-neutral by 2050, representing the first time this amount of money ($130+ trillion) has been on the table. Despite the high degree of interest, there are no concrete solutions to convert this goal into reality beyond having disclosures, standardized practices and regulations. Given the high stakes involved (especially for the billions of people in the Southern hemisphere who, according to Mr Samama, are at higher risk because of temperature and humidity), there is a strong need for a more straightforward approach.

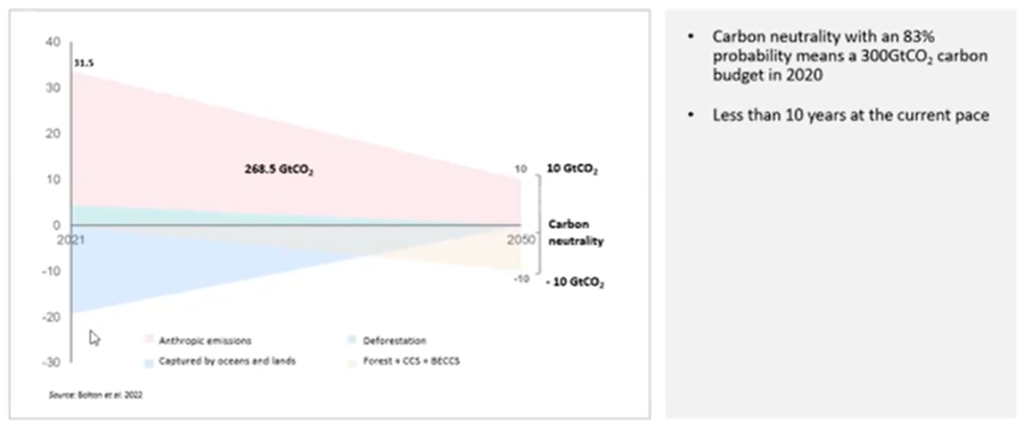

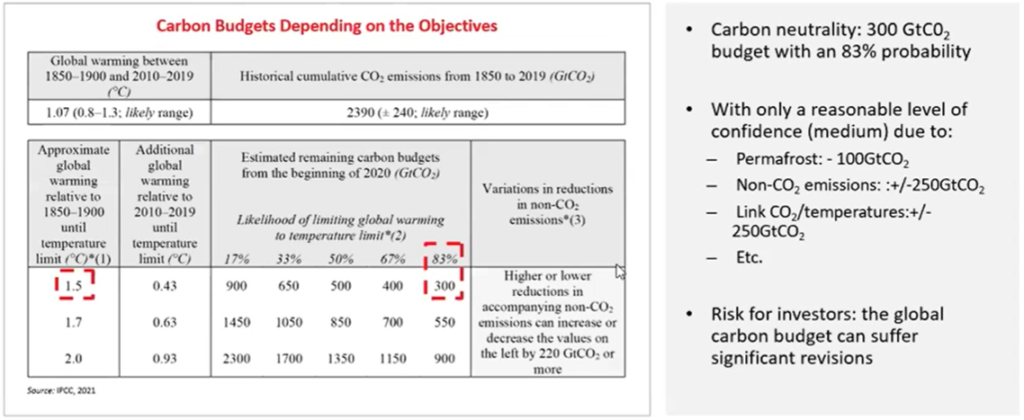

To that end, Mr Samama, along with Patrick Bolton and his team, have developed a paper that outlines how to concretely align portfolios with the net zero objectives that everyone now has in mind. Based on the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2020 announcement, to achieve carbon neutrality with a 1.50 C increase objective at 83% probability, we have a 300GtCO2 carbon budget in 2020 that is decreasing each year based on how much we spend:

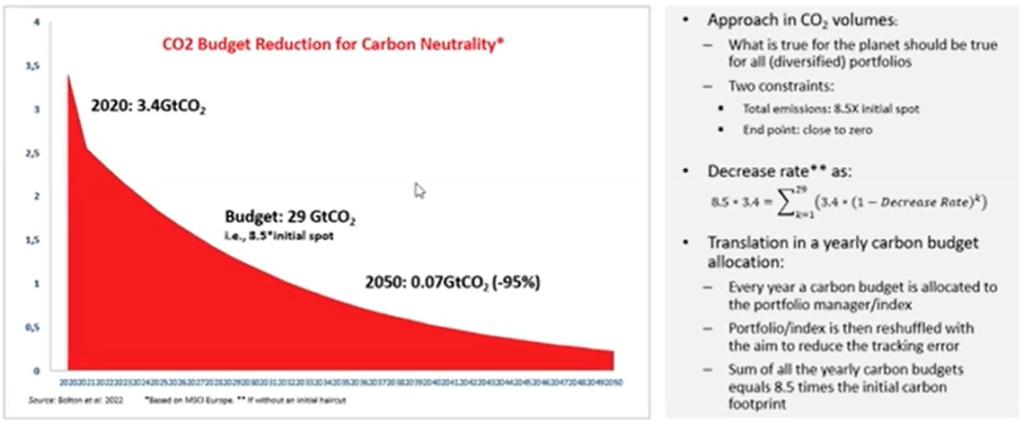

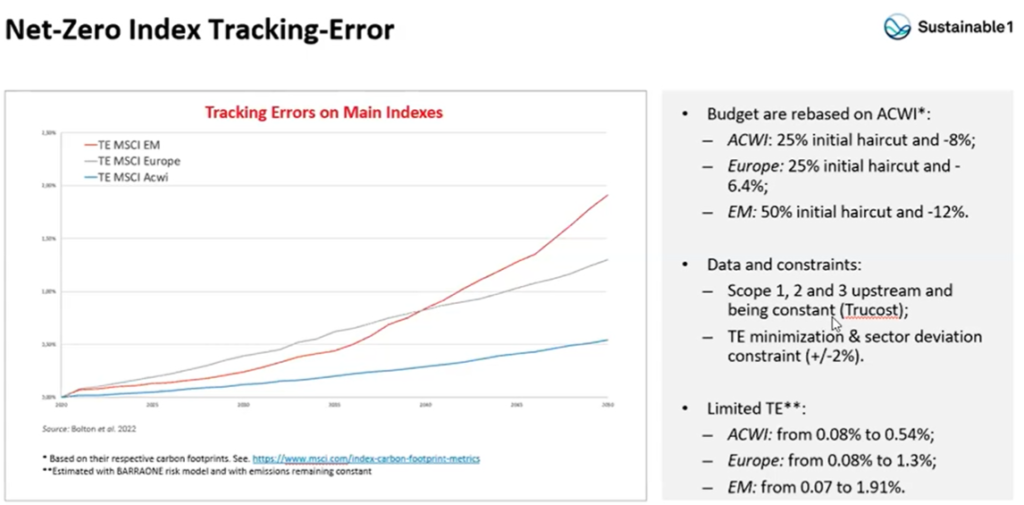

Based on the above chart, we know how much we (at the global level) can spend each year as we approach 2050 – Mr Samama and his team have gone one step further and applied this information at the portfolio level, whereby they have built a similar trajectory for any portfolio to which a carbon budget can be allocated and a developed roadmap for how the portfolio / index can fulfil the goal:

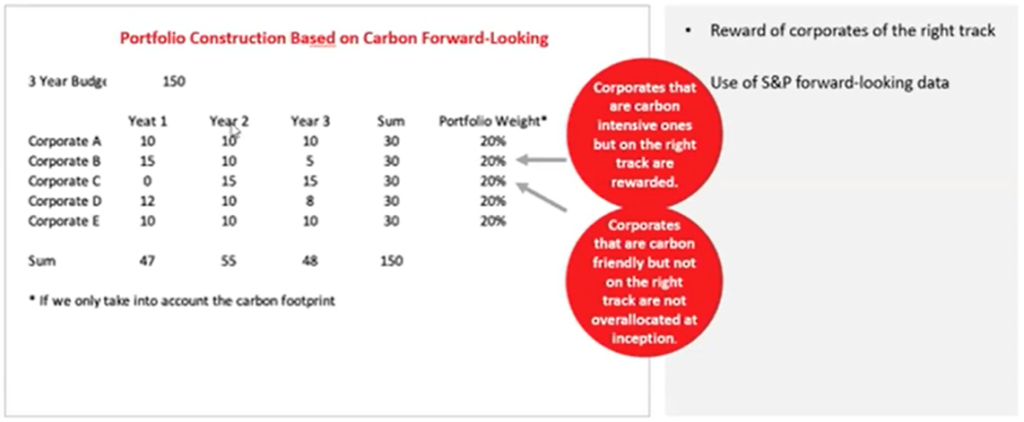

The data in this model is based on current carbon emissions, carbon earnings guidance disclosed by companies (based on their pipeline) as well as emissions data from the recent past (generally considered a good predictor for what to expect in the future). Corporate commitment is enforced by using forward-looking data to track performance: instead of allocating immediate-term 1-year carbon budget (which have proven to be neither enforceable nor actionable in terms of rewarding/punishing companies), a short-term 3-year carbon budget is allocated (e.g. from 2021-24) following which year-on-year corporate performance is tracked against that budget to reward corporates that are doing well and identify those that may need to do more to stick to their budget:

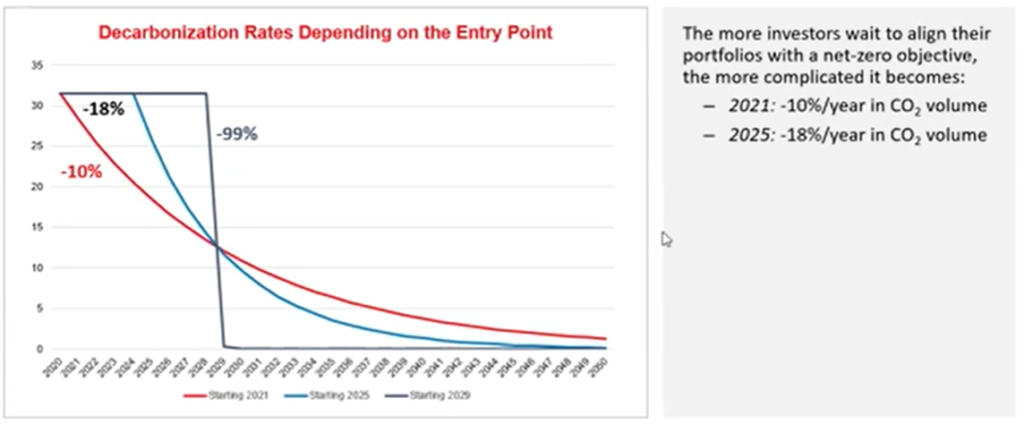

Using a short-term goal (vs. the full 30-year time horizon) is particularly important because there is immense time sensitivity in reducing carbon emissions. Based on IPCC’s model, a 10% reduction of carbon emissions every year from 2020 will be sufficient to achieve the goal by 2050:

However, as outlined in the chart above, the required % reduction in carbon emissions grows every year that it is delayed, such that if companies delay starting their reduction till 2025, the required reduction will be 18%. Thus, there is a high time cost of action, which is why short-term targets are necessary.

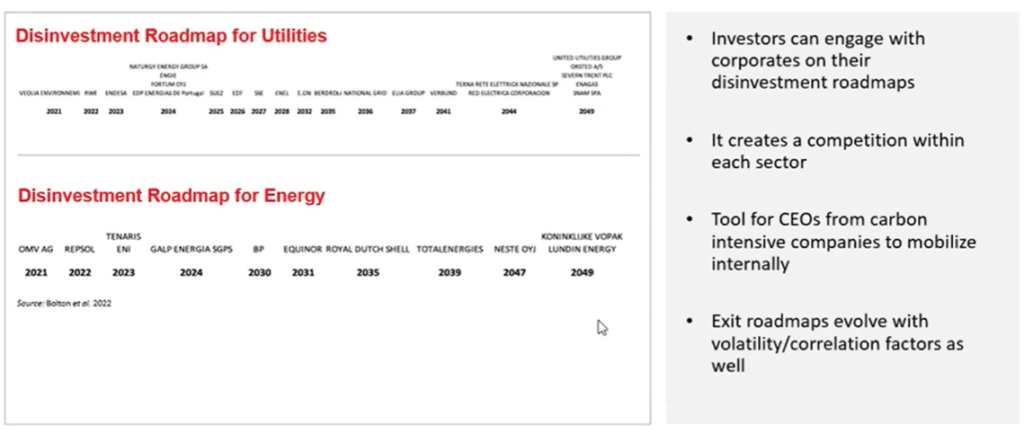

Another benefit of having multiple short-term targets (that work towards a longer-term target) is the ability for companies within each sector to pursue a disinvestment roadmap upon achieving their goals ahead of time:

This information is handy because it demonstrates by when companies can expect to achieve their goal and, once achieved, the impact of their disinvestment on the rest of their sector. Thus, knowing when companies can exit can help other companies re-evaluate their energy emissions and create healthy competition among companies to achieve net zero at the earliest.

So we now have an enforceable straightforward approach – is that enough?

While having this approach is a great first step, there continue to be lingering issues / uncertainties with achieving the goal of net-zero by 2050:

- Greater involvement from public sector: now that an enforceable approach has been developed, public entities can use public money to bring to the market concrete solutions (leveraging the proposed approach) that can unlock investment capabilities (e.g. setting up a green fund). It is a misconception that private funding is all that is needed to solve societal problems and it is no different for climate change – by providing investment vehicles (using public funds), public entities can incentivise greater transfer of dollars towards climate change efforts while using the approach proposed by Mr Samama and his team.

- Lack of standardised data: while we’ve collected data such as carbonized portfolios, an estimate on downstream carbon emissions for automakers etc. since at least 2011, there is a pressing need for more standardised data across portfolios, industries and countries to improve tracking and enforcement. While the time sensitive nature of action means that we (society and investors) must start immediately and adapt as data is available, there remains a need for improvement in the quality and standardisation of data, especially from data providers (who, Mr Samama notes, are a tricky part of the solution).

- Accounting for potential bias in impact: another major issue with tracking and reducing carbon emissions is an inherent bias in the data whereby an unfair burden may be placed on certain countries (especially developing countries) to achieve the necessary change. While Mr Samama and his team are accounting for such bias in their tracking efforts(see chart below), care needs to be taken to avoid excessively penalising the aforementioned countries.

- Lack of precision around value of permafrost, non-CO2 emissions and the link of CO2 and temperatures: the current estimates have been built around an assumed amount of permafrost, non-CO2 emissions, CO2 recapture by oceans and lands and, most importantly, the conversion between temperature and CO2 emitted/captured. If these estimates prove to be inaccurate, it’s possible that the budgets are misallocated.

Having said that, Mr Samama notes that this is likely to be more of an issue (if at all) when we are close to the final amounts of CO2 that we need to manage to meet the goal at 83% probability – until then, every Gt counts so this particular concern should not stop us from moving forward.

About Frédéric Samama

Mr Samama was formerly the Chief Responsible Investment Officer at CPR am, Amundi Group. He is the founder of the SWF Research Initiative and co-edited a book on long-term investing alongside Nobel Prize Laureate Joseph Stiglitz and he has published numerous papers on green finance. Mr Samama has advised the French Government in different areas (employee investing mechanisms, market regulation, climate finance) and has a long track record of innovation at the crossroads of finance and government policy. Over the past few years, Mr Samama’s action has been focused on climate change with a mix of financial innovation, research and policy making recommendations, being an advisor of Central Banks, Sovereign Wealth Funds or policy makers on the topic.

Nandini Mazumdar (MBA 2022) is a Co-President of the Tech & Media Club (and co-founder of the Fintech Community) at London Business School. Prior to the MBA, she completed her undergraduate studies in Econometrics and Political Science at New York University and worked at Mastercard Advisors, offering consulting and advisory services in the payments, fintech and technology sectors. Nandini is an intern for the Wheeler Institute, contributing to the creation of content that amplifies the role of business in improving lives.

The Wheeler Institute Climate Initiative seeks to understand, illuminate, and support the business community – individuals and systems – in understanding, responding and adapting to the challenges and opportunities that climate change presents. We have a particular interest on implications and actions for those in developing countries.

Professor Reichlin’s conversation with Frédéric Samama is the fourth event in a five-part webinar series with high-profile corporate leaders that aims to explore how public and private institutional investors can restructure capital offerings and risk management processes to reflect climate forces.