African History through the Lens of Economics: An introduction to African development and history

The Wheeler Institute’s open access online course, African History through the Lens of Economics, concluded with three plenary lectures covering the impact of foreign aid, the reasons why Africa can be optimistic about the future, and the importance of judging Africa on its own terms. The first session saw Bill Easterly, Professor of Economics at New York University, consider whether aid has worked in Africa, Célestin Monga, Visiting Professor of Economics at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, diagnose the causes and symptoms of ‘aid addiction’ and Dr. Mo Ibrahim, Founder and Chair of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation and the founder of Celtel, identify what needs to be done to stimulate development in the continent. In the second session, James Robinson, Reverend Dr. Richard L. Pearson Professor of Global Conflict Studies and University Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, and Chima J. Korieh, Professor of History and Director of African Studies at Marquette University, discussed how Africa’s latent assets – its social structure, cosmopolitanism and skepticism – could be utilised to bring about development in the coming years. In the third plenary session, Joe Henrich, Professor and Chair of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, considered which parts of the world were in fact WEIRD (possessed of uncommon beliefs), and what this could mean for Africa’s future development. Taken together, these three lectures made a powerful argument for those in the developed world to pursue more modest objectives and to allow Africans to determine their own destiny.

What do we mean when we talk about aid?

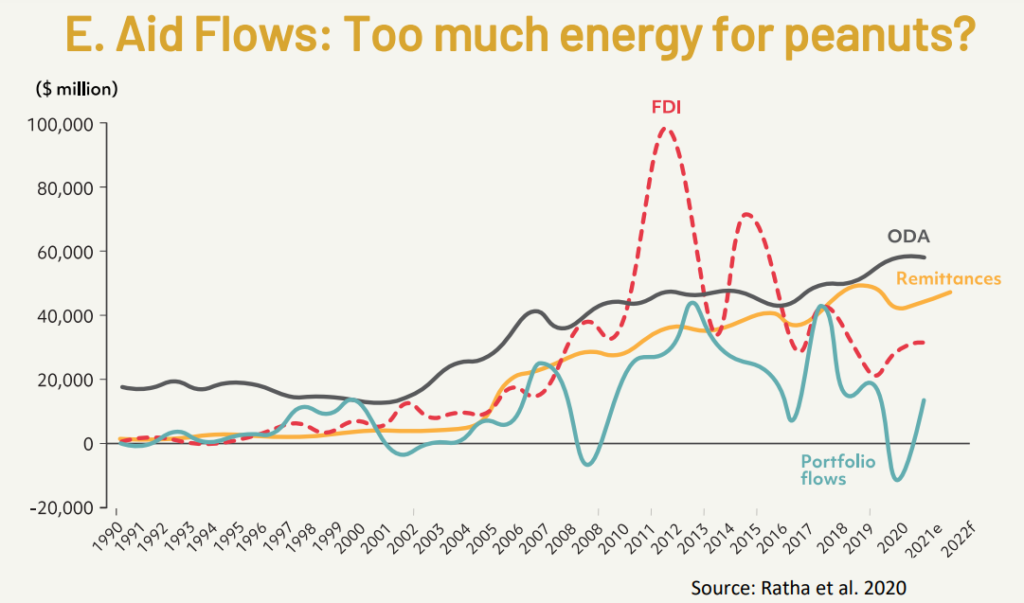

Célestin Monga summarised the OECD’s definitions of aid, or Overseas Development Assistance (ODA), which covers grants and loans with concessional terms, technical co-operation costs (including, for example, the salaries of foreign experts advising African governments) but excludes donations from the public and NGOs. He stressed that ODA actually represents only a small proportion of Africa’s annual GDP of $2-3tn and only part of the financial flows to the continent. The OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) recorded $58bn of ODA to Africa in 2019-20. Also significant for the continent as a whole are FDI, remittances, and portfolio flows.

Nonetheless, aid has a politically prominent place in the minds of donor countries and their populations, one reason for which is undoubtedly the gap between historical expectations and outcomes.

The failure of the developed world’s Big Push and the rightful place of aid

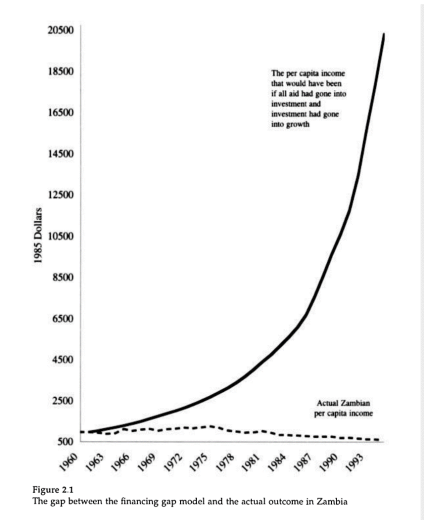

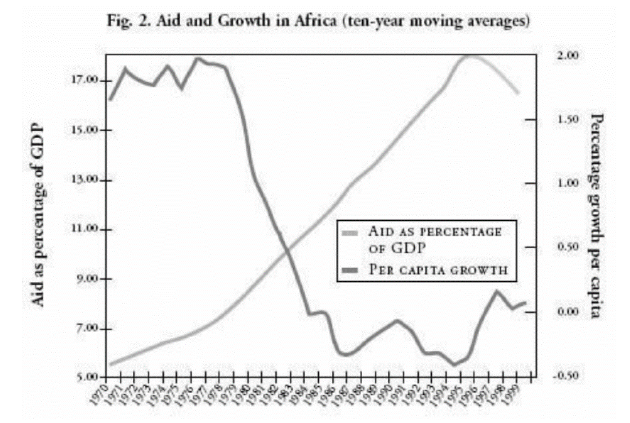

Bill Easterly picked up on this point by explaining the Big Push – the idea that African countries were in a poverty trap from which they could not escape without receiving initial momentum in the form of foreign aid and that this process would lead their economies to higher investment and self-reinforcing growth – and its importance to World Bank policymakers in the 1980s (of which he had been one). He then observed that, to say the least, the optimistic forecasts of growth had not materialised as expected, with per capita GDP growth falling through the period despite steadily increasing levels of aid and per capita income remaining flat compared to a forecast twenty-fold increase. He emphasised that this is not to say that aid caused these declines, just that it did not stimulate growth as modelled and assumed.

What was the cause of this failure? Professor Easterly’s contention was that insufficient attention was paid to the incentives – for public officials to deliver public goods and for businesses to provide private goods – that could be generated through effective political and economic institutions, and that donors were either unaccountable for results or self-interested.

The problems of poor governance

As an example of this self-interest taking precedence over considerations of political and economic freedom, he noted that there had been a 300% increase in the average annual aid provided to countries ranked in the lowest quartile for freedom in the period following 9/11, compared to 30-40% increases across the other three quartiles. The US military’s Africa Command made allies in oppressive rulers in Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia and Somalia in the same period.

Dr Mo Ibrahim also identified poor governance – among both donors and recipients – as the most important factor in the failure to translate aid and investment into development. He reminded the audience that fast decolonisation was followed by a period of intense geopolitical rivalry in the Cold War that saw contributions advanced on the basis of political allegiance as much as competence. Incidentally, the current geopolitical environment, therefore, with its prospect of increasing regionalisation and confrontation, was a cause for concern. African governments had also contributed to the problems, and he told the anecdote of a World Bank mission to a nearly bankrupt country being treated to a meal in the Presidential palace cooked by a three-Michelin starred chef recruited from a Parisian restaurant and served by white-gloved waiting staff as an exemplification of irresponsible government.

Dr Ibrahim felt, however, that an excessive focus on corruption could distract from other issues of poor governance. He reminded the audience that aid to Africa was recently just over $50bn a year, but that illicit financial flows out of the continent were estimated at $89bn annually by the UN, and up to $107bn by others. Of this amount, only $6-7bn is corruption, with the majority represented instead by corporate profit-shifting and mis-pricing. He encouraged greater action on tax at a global level to address these issues.

Other side effects of an addiction to aid

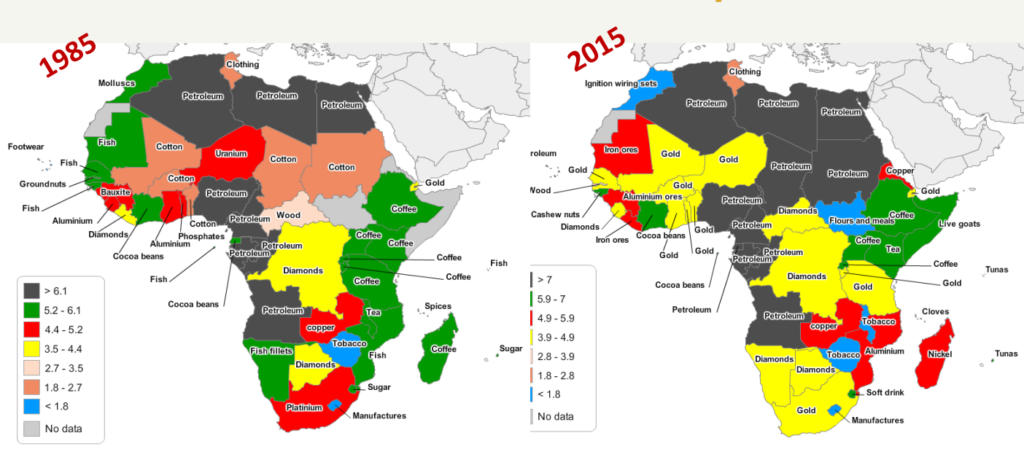

Célestin Monga diagnosed the symptoms of what he described as an addiction to aid in African economies. First, he argued that it had resulted in the pursuit of poor policies and bad ideas. He compared maps of the most important exports of African countries in 1985 and 2015 and pointed out that in 2015 in most countries it remained a commodity, with little structural transformation having been achieved in the intervening thirty years. This has left the economies at risk from fluctuations in commodity prices and un-resilient in the face of shocks.

He also noted a continuing romanticisation of poverty – the images of women with babies on their backs and heavy loads on their heads – despite this being the precise condition these aid flows were supposed to address, and pointed out that what Bill Easterly has described as the ‘tyranny of experts’ had not significantly improved living conditions for many Africans. As Ali Mazrui observed, “In many parts of Africa, it is still much easier to find a bottle of beer than a bottle of fresh water.” Similarly, fiscal revenue as a percentage of GDP remains comparable in 2020 to the figures twenty years earlier, and is significantly worse in some countries.

What to do about aid?

Professor Monga noted that aid remains a controversial topic even amongst academics, summarising the positions of four leading economics as shown below.

Bill Easterly’s presentation concluded that the key actors in African development are not donors, but farmers, producers, entrepreneurs and exporters; success will come from the energy and commitment of these African citizens, not from outside. He believes there is still a place for aid, but only in pursuit of more modest objectives, such as public health initiatives like the successful distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets as a prevention against malaria.

Mo Ibrahim argued that donors and development agencies had originally shied away from making substantial infrastructure investments in Africa, only really doing so once China offered a credible alternative. Even now, however, he argued, their focus is too narrowly on financial return and not sufficiently on investment as a means of job creation and sustainable, long-term development. Like Bill Easterly, he sees a role for funders in supporting training and education for the continent’s young people. He urges a particular focus on brining the 600 million Africans currently without access to electricity onto the grid and improving the resilience of the agricultural sector to address food insecurity arising from climate change and the war in Ukraine.

Célestin Monga’s own opinion is represented by a pragmatic approach of New Structural Economics that involves identifying comparative advantages, removing constraints for firms in these industries or bringing latent comparative advantages into existence, scaling up self-discovery by private firms, stimulating industrial clusters and providing limited subsidies to compensate for externalities.

Africa’s latent assets

James Robinson and Chima Korieh developed some of these ideas in the second plenary session. They started by asking the audience to imagine the assessments that could have been made of China’s economic history and development in 1978, just before forty years of 10% annual growth. Some commentators would surely have pointed to dysfunctional fiscal and granary systems, prominent examples of corruption and misgovernment, the failures of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution; others might have pointed to the norm of meritocracy and the historic selection of the pre-modern elite through competitive examination as a powerful social principle on which to base entrepreneurship, innovation and rapid growth.

Similarly, though the dominant narrative about African development is one of problems and obstacles, we might now be able to identify various latent assets that could be utilised to drive growth in the coming decades. Robinson and Korieh identified three such assets: a society responsive to individual achievement; a tradition of resisting authority and being skeptical to authority that represents a strong basis for building inclusive and accountable political systems; and a cosmopolitan population that speaks multiple languages and is comfortable dealing with differences.

Achievement-based social mobility

James Robinson outlined research on perceived and actual levels of social mobility in Africa. Afrobarometer survey data on perceptions of individuals about their own income and that of their parents show high variability, with only about 20% of people assessing themselves in the same income decile as their parents, compared to over 50% in Latin America and 40% in the U.S., suggesting that Africans feel social mobility available to them to be higher than people elsewhere. In terms of actual rather than perceived mobility, he reminded us of the work of Elias Papaioannou and Stelios Michalopoulos on educational mobility [see Week 10 summary]. Though there is a lot of heterogeneity in this area as in so many others, parts of the continent, for example Kenya and Ghana, have similar levels of mobility as parts of Western Europe.

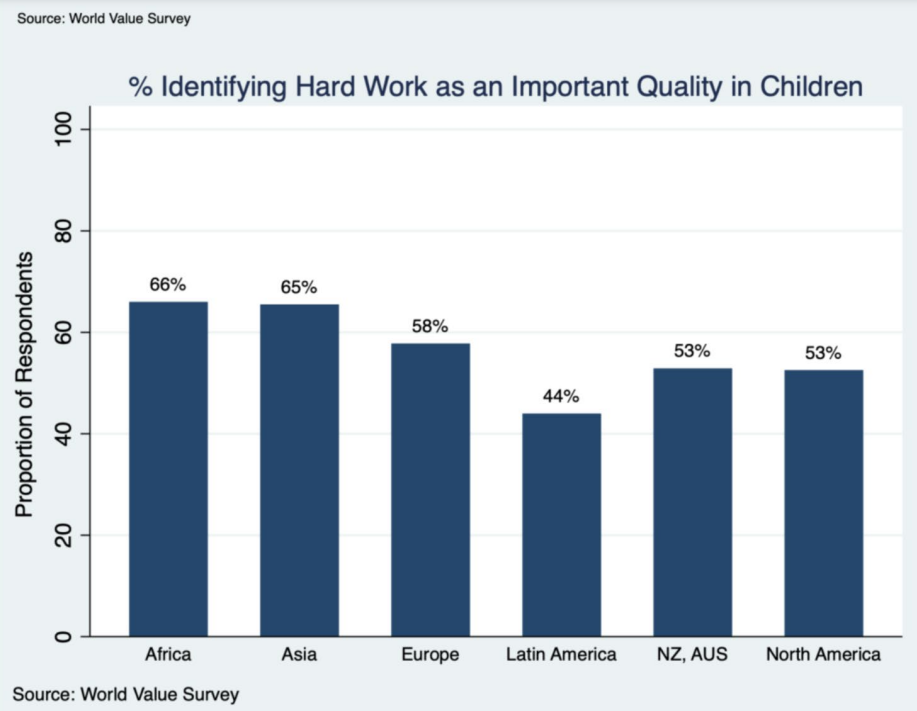

Two World Bank survey results support these findings. First, when asked whether hard work or luck and connections are more important to advancement, a higher proportion of people from Africa report hard work than from any other region. Second, when parents are asked to identify the values they wish to inculcate in their children to give them a chance of success in life, a higher proportion of Africans (66%) select ‘Hard Work’ than any other region.

Taken together, these datapoints suggest a society that is ripe for entrepreneurship.

Skepticism of power

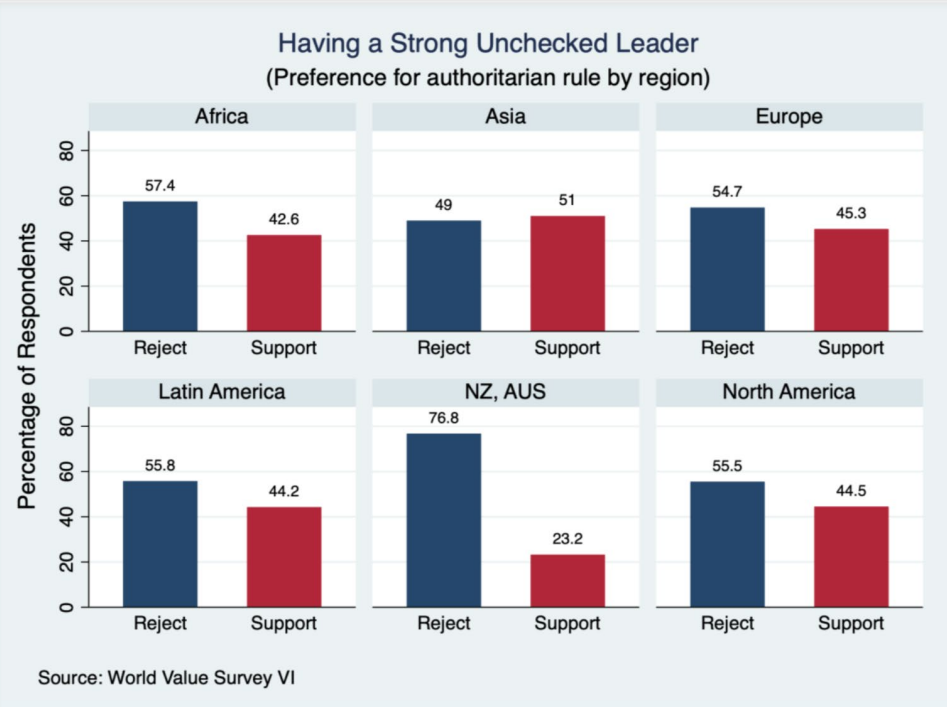

The second latent asset is skepticism about power. Despite the high-profile examples of poor governance discussed in previous lectures and frequently cited in the Western press, Africans are in fact more likely to reject the idea of living under a strong leader who does not respect democratic elections and parliament than people in any other region except Australia and New Zealand and are less favourable to one-man rule.

In general terms, Robinson and Korieh suggested that this skepticism emerges from African ‘social contracts’ that governed life before the colonial administrations (discussed in the second lecture of the series). As so often seen in the course, though, here too heterogeneity is an important consideration. Recent research has broken down attitudes to one-man rule in Nigeria by ethnicity. We can see that groups like the Igbo, Tiv and Ibibio, which were stateless, disapprove much more strongly of one-man rule than groups like the Fulani or Hausa, which had more centralised institutions. This suggests that some parts of the continent are likely to be particularly receptive to inclusive governance.

Robinson’s conclusion on this subject was that, though there are challenges to building modern state institutions in Africa, there is reason to believe that when it happens, more functional states than in other regions will be the result.

Cosmopolitanism and women’s empowerment

Chima Korieh explained the last of Africa’s latent assets: cosmopolitanism. Africans are used to dealing with diversity, one consequence of which is multilingualism, as was outlined in Christopher Ehret’s first lecture in the series and picked up frequently in subsequently lectures, for example in the Murdock map of ethnolinguistic groups. There are reasons to think that this could improve inter-group relations, leading to a more inclusive society.

Robinson and Korieh site cosmopolitanism as part of a deeper humanistic ontology and inclusiveness that exists in Africa, where people are more valuable than things. They gave as an example the Igbo notion that everyone has a value and is good at something, as exemplified in proverbs such as, “Let the kite perch and let the eagle perch.” This radically egalitarian worldview can be related to Michael Sandel’s notion of contributive justice and its potential for use in underpinning political and economic development has been explored by Francis Njoku at the University of Nigeria.

A related element of African society is the empowerment of women. Fascinating historical examples include the 1929 Aba Women’s War against British colonialism in southern Nigeria and the ‘dual sex’ political systems which had parallel political institutions for men and women with a male king and a female queen who were completely unrelated. As Ifi Amadiume explains in her book on the Nnobi, Male Daughters, Female Husbands, gender was culturally constructed in this group, with women able to take other women as wives and daughters able to take on male roles, and the most powerful political role being the Agba Egwe, the oldest woman in the society. These divisions extend as far as having responsibility for separate crops, with women growing cocyams and men yams.

When faced with a globalised world that requires collaboration, acceptance of others and flexibility, and that demands equality and inclusiveness, African societies are well placed to succeed.

Why it is actually European and American societies that are WEIRD

In the third plenary lecture, Joe Henrich also considered the psychological and cultural variation we see across the world. His work has taken an evolutionary approach to thinking about how people learn from each other, looking at cultural products such as tools, practices, norms and languages, and at cultural psychologies encompassing visual processing (how one sees the world), self-regulation, pro-social behaviours and spatial cognition (how one navigates the world).

Among social norms, he has examined variations in levels of in-group and out-group trust, individualism and moral universalism, which have outcomes for how groups innovate, respond to strangers and so on. An important finding is that the aggregated set of beliefs common in Western Europe and the Americas – bilateral descent, rarity of cousin marriage, monogamy, nuclear family preferences and neolocal residence – are highly unusual on a global scale. Indeed, they are almost uniquely WEIRD (Western, Educated, Intelligent, Rich and Democratic); it is the West that is unusual, not the rest of the world.

One of Henrich’s applications of this research is in seeking explanations for divergent global economic growth patterns. His mechanism leads from culture to formal institutions and openness to trade and new ideas and then to economic growth. He finds causes of innovation in interactions between individuals who trust each other, in social factors such as urbanisation and immigration, and in psychological factors such as co-operation with strangers, individualism and non-conformism and preference for novelty.

He concludes that kinship-based institutions and societies with higher kinship intensity are associated with lower economic growth. In the Q&A after the session, Nathan Nunn asked what the effect of colonial powers breaking down the pre-existing, kinship-based institutions might have been on subsequent African development, whether the changes were deleterious or potentially beneficial. In reply, Henrich pointed to the lack of compensating institutions that could facilitate anonymous exchange similar to the medieval European guilds as one possible reason why African development had not followed the trajectory of pre-industrial Europe.

It remains an open question how Africa’s cosmopolitan and egalitarian societies can best foster innovation in the coming years, but one that is important for the continent’s development path.

Reasons for optimism

At the close of his lecture, James Robinson concluded that many factors constitute reasons for optimism when considering this future development path. In the West, we all too frequently focus on the usual suspects of bad governance, a lack of accountability and corruption. While important, these obscure a long history of Africa developing hybrid solutions to political and economic problems. Africa’s real assets are its people and unique history, attitudes, culture, creativity, energy and institutions; if elements such as the autonomous political role of women and the collectivist and inclusive nature of society can be harnessed, African development could follow a more promising path than is often assumed and the coming decades may mirror the Chinese growth miracle of the last forty years.

African History through the Lens of Economics is an open-access, interdisciplinary lecture series to study the impact of Africa’s history on contemporary development by the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development. This course is led by Elias Papaioannou (London Business School), Leonard Wantchekon (Princeton University), Stelios Michalopoulos (Brown University), and Nathan Nunn (Harvard University and supported by CEPR, STEG and the European Research Council. The course ran from February 1 to April 13 of 2022 and has attracted more than 27.000 registrations. For more information visit the course website.

David Jones (MBA 2022) is a Classics graduate and has worked as a teacher in Malawi, an accountant at Deloitte and in the finance function at the Science Museum in London. He completed an internship with the Wheeler Institute’s Development Impact Platform in Zambia over summer 2021 and is now continuing as an intern for the Wheeler Institute, contributing to the creation of content that amplifies the role of business in improving lives.