African History through the Lens of Economics: An introduction to African development and history

The penultimate lecture in the Wheeler Institute’s open access online course, African History through the Lens of Economics, considered the impact of education on social mobility in Africa. David Laitin, Professor of Political Science at Stanford University, Leonard Wantchekon, Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University, Gábor Nyéki, Assistant Professor at the African School of Economics and Elias Papaioannou, Academic Director of the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development, presented introductions to their research in the area. The session was moderated by Jacien Carr, PhD student with the Department for History at SOAS, University of London.

Three different perspectives on African education were presented. First, David Laitin discussed his research into the effects of prioritising official languages in African education systems at the expense of indigenous alternatives. Then, Leonard Wantchekon considered how schooling affects the economic outcomes of first, second and third generations in families and villages in Benin and Nigeria. Finally, Elias Papaioannou explained how we can map educational and social mobility across the continent to identify the areas of opportunity, where children can do better than their parents.

Indigenous language teaching

David Laitin began by reminding the audience that the neo-colonial reality in sub-Saharan Africa is that in no country is an indigenous language in a pre-eminent position in secondary education, upper levels of the civil service or business. This situation persists despite the efforts of first-generation leaders to promote indigenous languages – some examples of which included Julius Nyerere’s translation of Julius Caesar into Swahili, the changes in the names of Ghana and Burkina Faso, and the creation of an entirely new script, Cismaaniya, in Somalia – and despite repeated calls from intellectuals like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in Kenya to prioritise indigenous language culture and education.

Professor Laitin then introduced a paper (Laitin and Ramachandaran, 2016) that looked at how an individual’s exposure to an official language and the linguistic distance between the official language and the individual’s mother tongue affected educational, health, occupational and wealth outcomes. The concept of linguistic distance captures the difference between languages of different families and groups; sub-Saharan African countries have an average score that is far higher than for any other region in the world, meaning that there is a near maximum disconnect between African languages and the languages used in administration and education.

There are many reasons why post-independence African countries have not closed this gap, including the lack of a written tradition in many indigenous languages, vested interests in the political and bureaucratic classes, parents’ aspirations for their children to be conversant in official languages, and competing economic and political priorities, as covered in Ericka Albaugh’s State-Building and Multi-Lingual Education in Africa (2014). The consequences are both cultural – for example, a field experiment in Wajir found that individuals made claims based on authority more frequently in English than Somali – and socio-economic, with increasing ADOL (average distance from the official language) resulting in lower cognitive test scores, life expectancy, GDP and output per worker. The channels that determine these results are two-fold: exposure to the official language in the home and linguistic distance; and African students are burdened with low exposure (for example, because their parents do not speak English at home) and high distance (because their languages are unrelated to English).

Professor Laitin concluded, however, by observing that linguistic diversity is not destiny. He cited Miguel (2004), which compared Busia in Kenya and Meatu in Tanzania, similar regions in terms of linguistic diversity but with differing levels of promotion of indigenous languages, and found that issues of declining trust could be reduced through high ethno-linguistic diversity. Similarly, several of the smaller European states have shown the benefits of combining support for local languages with instruction in more widely used languages.

The legacy of colonial era educational investments

Leonard Wantchekon then introduced a fascinating, long-term (12-year) investigation into the externalities of education and the mechanisms of persistence, particularly across generations. The results were strong, showing that education leads to higher living standards, less reliance on subsistence farming and wider social ties and that village-level externalities or spillover effects are key to this process, i.e. that those from a village with a school do better, even if their parents or grandparents did not attend school themselves. These effects come about primarily from an improvement in attitude and self-reliance among inhabitants of the village.

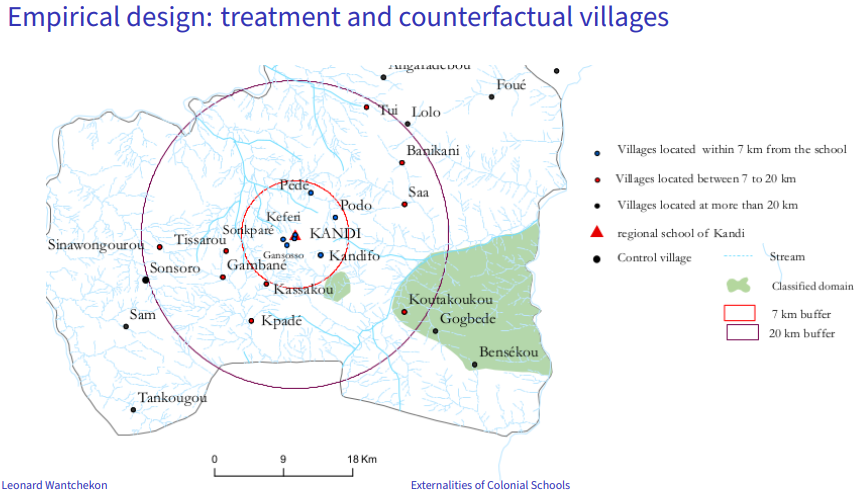

The study makes use of an innovative methodology of backward sampling to ascertain whether members of preceding generations had attended school and relies on the quasi-random establishment of schools across Benin; it categorises individuals between those who attended schools within three years of their establishment, those who lived in villages within 7km of a school (sub-divided between those villages where someone attended school and those where no one did), and control groups 7-20km from the nearest school. Socio-economic outcomes were compared between these groups, then their descendants were identified and also compared. One of the regions used for testing is shown in the diagram below.

As would be expected, there is a large gap in outcomes in the first generation between those who went to school and those who did not. By the second generation, however, the gap shrinks significantly between the descendants of those who went to school and those who did not, providing evidence of social mobility for the families of those who lived near a school, even if they did not themselves attend. By the third generation, those whose parents were low income have a 70% chance of doing better than their parents in villages near to schools, compared to 40% for low-income families in control zones.

Gábor Nyéki then explained how this methodology has been extended to Nigeria. In Benin, the cultural environment was somewhat homogeneous, whereas Nigeria offers the chance to investigate the effects of gender and religion in a more heterogenous setting.

Mapping educational mobility

Finally, Elias Papaioannou introduced two papers co-authored with Alberto Alesina (to whose memory the presentation was dedicated), Sebastian Hohmann and Stelios Michalopoulos that considered respectively the sizeable differences in education and wellbeing within regions and across the continent (Alesina et al., 2021) and the role of religion in determining these differing outcomes (Alesina et al., 2020).

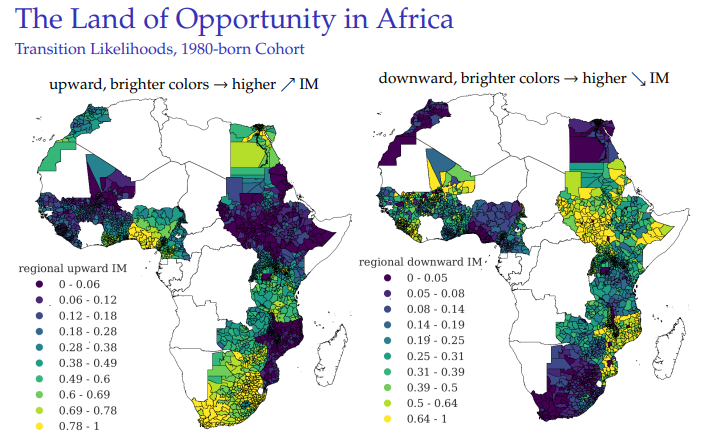

Intergenerational mobility – here defined as the likelihood of competing primary school if one’s parents did not do so – is greater in countries with higher levels of literacy in previous generations and is persistent. The research is based on representative samples from censuses, capturing nearly ten million people across 27 countries and 2,846 regions. The results (see figure below) show striking differences in both upward and downward mobility across the continent. This is important because, as first identified by Williamson, lower mobility correlates with higher inequality.

To investigate whether these regional factors are causal – or whether they represent spatial sorting – the team made use of an interesting methodology developed by Chetty and Hendren (2018) of looking at families with children of different ages who move between regions to identify whether the regional effect was larger in those who were younger when they moved and so who were exposed to the new region for longer. The results showed that regional childhood exposure has effects irrespective of the family’s religious affiliation, that there is sizeable spatial sorting for both Christians and Muslims, and that the effect of regional exposure is greater for girls.

The second paper looked at the effect of religious affiliation on intergenerational mobility. There are differences in outcome related to religious affiliation, with Christians doing better than Muslims and traditional African religions. Possible reasons for these gaps could include household characteristics, economic features and regional factors. This area of research is still developing, but the latest conclusions are that Muslims and Animists generally reside in less developed regions (with lower upward mobility); that correlations between regional features and mobility are similar across religions; that regions matter equally for female Africans of all religions, but less for male Muslims; and that Muslims fare worse in areas where they are in the majority or a significant minority, though this is not the case for Christians or Animists.

Future research opportunities

Taken together, the three presentations provide a fascinating overview of recent research into the role of education on social mobility across the continent, whether this be the importance of indigenous language instruction, the inter-generational impacts of education or the heterogeneity of educational and social opportunities across the continent, its regions and religions. Given the strong correlations between intergenerational mobility and economic outcomes, understanding these issues is of fundamental importance to the continent’s future development.

Professor Papaioannou concluded by noting that there are still many open questions in this area that could form the basis of future research. These include the role of educational policies, reforms and school construction; risk-sharing mechanisms; seasonal and permanent migration; and case studies, perhaps on Africa’s mega cities.

African History through the Lens of Economics is an open-access, interdisciplinary lecture series to study the impact of Africa’s history on contemporary development by the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development. This course is led by Elias Papaioannou (London Business School), Leonard Wantchekon (Princeton University), Stelios Michalopoulos (Brown University), and Nathan Nunn (Harvard University and supported by CEPR, STEG and the European Research Council. The course ran from February 1 to April 13 of 2022 and has attracted more than 27.000 registrations. For more information visit the course website.

David Jones (MBA 2022) is a Classics graduate and has worked as a teacher in Malawi, an accountant at Deloitte and in the finance function at the Science Museum in London. He completed an internship with the Wheeler Institute’s Development Impact Platform in Zambia over summer 2021 and is now continuing as an intern for the Wheeler Institute, contributing to the creation of content that amplifies the role of business in improving lives.