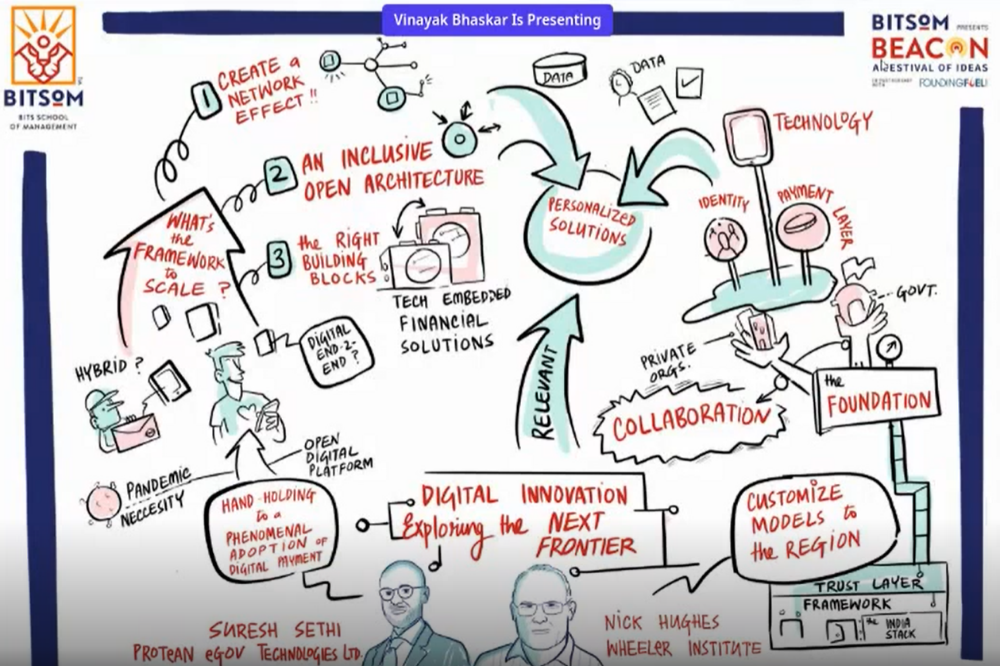

What can the success of M-Pesa in Kenya and India Stack in India tell us about the future of digital innovation in the developing world? Nick Hughes, co-founder of M-Pesa & M-Kopa, currently Founder and Managing Director at 4RDigital and Executive Fellow at the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development, joined Suresh Sethi, former Managing Director & CEO of the Vodafone M-Pesa team and currently Managing Director & CEO at Protean eGov Technologies Ltd., on a panel titled “Digital Innovation – Exploring the Next Frontier” at the BITS School of Management’s BEACON Festival of Ideas.

Uptake of digital products has grown tremendously in recent years, catalysed by the pandemic

Historically, the launch of digital products has been met with scepticism and hesitation. In developing countries, this attitude was primarily driven by disbelief in the lasting nature of digital products and distrust for how they work. Having said that, following a concerted effort by key industry players to ensure that the average user understands how digital products work, digital adoption has grown tremendously. This has been especially true during the pandemic where the need to avoid physical contact and to conduct business online has increased our dependence of digital technology. As Suresh and Nick highlight, a key reason for the success of digital adoption and usage has been having an open architecture and enabling interoperability between systems/platforms. They believe that the future of business and technology is embedded in open architecture, open standards and open exchange across systems/platforms/providers..

Solutions such as M-Pesa and India Stack have revolutionized financial inclusion, digital connectivity and mobile money services– what can we learn from them?

The success of M-Pesa in Kenya demonstrates how a compelling proof point can ensure that your product truly stands out and sticks. In this case, M-Pesa was able to overcome significant financial inclusion challenges through digital technology and online payments. However, it would be incorrect to assume that the M-Pesa model would apply in any setting, without considering framework conditions in different contexts. For example, a significant driver of M-Pesa’s success in Kenya was that Vodacomm (the organization that launched M-Pesa) had majority share of the local telecom market (62% market share when M-Pesa was launched, which grew to 90% over the years). Being a single player with a significant hold on the ecosystem, empowered Vodacomm (and therefore M-Pesa) to deliver financial inclusion/payments on its platform and achieve scale and success. Conversely, in a country like India that previously had a fragmented telecom market and low interoperability, it would be difficult to push a product like M-Pesa if users are unable to move money across platforms/providers.

India has taken significant steps in recent years to make interoperability possible by introducing open technology platforms and standards through India Stack. India Stack enabled India to make advancements in the last 10 years that would have otherwise taken 46 years in a typical cycle of financial inclusion. So why has India Stack worked so well? According to Suresh, there are a few reasons underpinning its success: firstly, the India Stack ecosystem is built on providing the population with a digitally verifiable identity. This technology has granted one billion Indians with a verifiable identity, which allows them to access services within the formal economy e.g., get a bank account, access formal banking services etc, which is a critical step towards financial inclusion among historically excluded segments. Secondly, by setting up policy measures and regulations that took advantage of opportunities provided by technology and the Internet, the Indian government was able to build on newly created digital identities and offer products/services. Drawing a greater portion of the Indian population into the formal banking sector. This was achieved primarily through the opening of bank accounts, leading to a 700% increase in the number of bank accounts from 2010 to 2019. Finally, the availability of technology that enabled to people to make payments, move money across accounts/institutions. By embedding payments into the infrastructure and linking a myriad of standalone financial institutions, India Stack was successful in boosting digital sign-ups and usage. Simultaneously, the government’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) initiative (a mobile application that connects multiple bank accounts and “merges several banking features, seamless fund routing & merchant payments into one hood”[1]) was able to connect 282 banks, financial institutions and big tech companies with a user’s most basic details. This convergence of the banking and tech sector based through an open architecture and existing user information was further instrumental in driving the success of UPI and India Stack.

Looking ahead: What is next for financial inclusion and digital innovation in developing countries?

On achieving scalability:

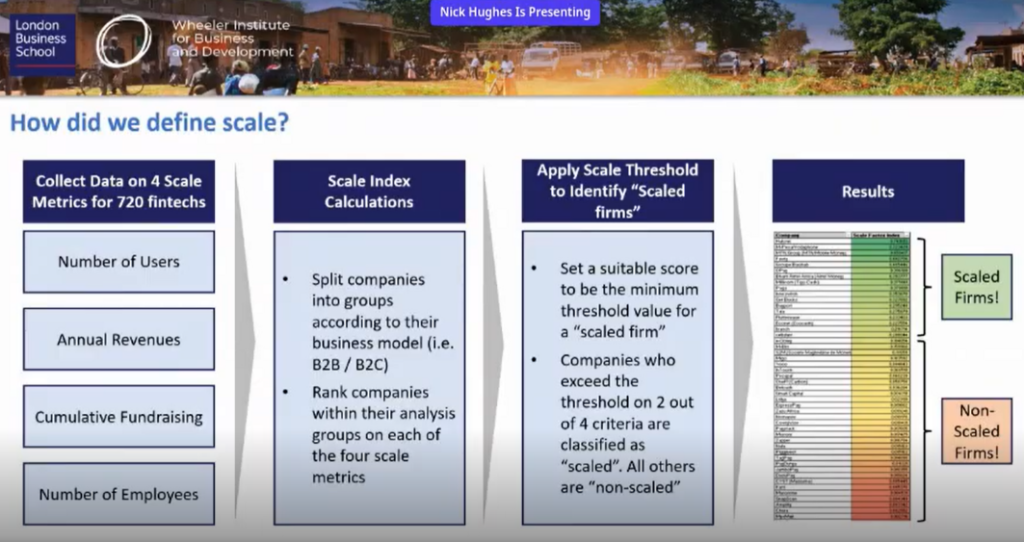

While M-Pesa and India Stack are examples of scalable, digitally innovative financial solutions, both Nick and Suresh believe that we cannot definitively say what drives scalability in developing economies. In Africa, based on an ongoing research project called DigitalXScale (in collaboration with the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development), Nick hypothesised that there is a high chance of achieving scalability when there is a lack of formal brick-and-mortar infrastructure, widespread availability of 4G/5G network and high smartphone penetration. However, upon developing a unique index methodology and applying it to 720 fintechs, it was revealed that scale in Africa is not only rare but also concentrated as only 5% of the analysed fintechs had achieved scale (based on this methodology) and most were concentrated in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya[2].

Further analysis revealed that there is still a need for better operational ability and the proverbial “boots on the ground” (in terms of a network of agents, in-person onboarding, access through feature phone etc.) to achieve scale in Africa. India is in a similar position whereby the dominant model is still through assisted services (i.e., leveraging intermediary personnel such as agents, tellers, customer service representatives etc.) versus self-service services (i.e., leveraging chatbots, virtual agents, IVR etc.). Therefore, there is a while to go before the financial services ecosystem becomes entirely digital. The more important need, as noted by Suresh, is to create an inclusive architecture that takes everyone forward, even if there continue to be assisted services.

On embedding finance in the overall value chain:

Embedded finance is the practice of adding payments capabilities in different value chains. As Suresh notes, with the ongoing convergence of banking and technology, payments are likely to get commoditized such that it is no longer a differentiator but is an ambivalent part of general interactions (i.e., whether with financial institutions or through social media). As this happens, traditional financial institutions will no longer have a stronghold on the payments space and other players such as social media companies, big tech and fintech companies will be able to embed payments in their offering and deepen usage without involving traditional banking. Rather than eliminating banks, Suresh believes a bigger difference can be made through a system like UPI, which is still linked with traditional bank accounts and thus, does not exclude traditional banking players from the impending growth in the industry.

Beyond the evolution of payments, another interesting development within embedded finance is offering more tailored credit services to informal micro-retailers e.g., mom-and-pop shops and other tiny businesses that are equipped with a POS (typically a smartphone) and can process transactions. As Nick notes, the focus has historically been on building services for consumers, but there is an opportunity to identify other groups and segments to whom similar financial services can be offered – one opportunity is the micro-retailer network for whom there is a sizable, untapped space to develop mobile-led commerce. Suresh doubles down on this when he talks about the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) industry in India – despite being a growth engine for the country, driving 30% of India’s GDP, only 10% of MSMEs have access to formal credit, which indicates a strong need for novel forms of lending (outside conventional services).

Nick postulates that one such evolution of financing options can be flow-based lending wherein financial institutions build/offer financial services/ products that are linked to/based on transaction data on the platform. An example of such a form of lending in action is M-Shwari, a savings account product that was launched onto the M-PESA platform where institutions could build profiles of individual customers using transaction data and develop products that directly address their needs. Similarly, M-Kopa, another platform launched by Nick, allowed customers to access clean energy solutions (specifically a solar power pack) through a unique form of asset financing whereby the company would connect the equipment for free and collect small payments from customers for ongoing usage. While it entailed a significant amount of management (especially since the payments would be made digitally), it opened a huge business opportunity to offer unique financial services i.e., loan for small business, cashback to M-PESA account etc. based on how regularly these customers were making their payments on the first secured asset/connected product. In this way, finance became an enabler to solve energy problems, and the M-Kopa team was able to scale up to over 1M customers. As Suresh notes, India is looking into similar ways to leverage transaction history and account linking to empower customers to access differentiated financial services. The launch of the “account aggregator” entity by the Reserve Bank of India as well as the creation of the open credit network allows customers to not only own and use their data but also to use their payment history to access the appropriate products / services. In general, Suresh believes that traditional incumbents may struggle to keep up with the more nuanced forms of lending and financial services as their risk appetite is different vs. that of new players, leading to a difference in ticket size, loan duration etc. Since the shift to digital is also decreasing the cost of distributing credit, it is likely that, as the lending industry changes, there will be a whole set of new players coming in to fulfil this need end-to-end.

Nandini Mazumdar (MBA 2022) is a Co-President of the Tech & Media Club (and co-founder of the Fintech Community) at London Business School. Prior to the MBA, she completed her undergraduate studies in Econometrics and Political Science at New York University and worked at Mastercard Advisors, offering consulting and advisory services in the payments, fintech and technology sectors. Nandini is an intern for the Wheeler Institute, contributing to the creation of content that amplifies the role of business in improving lives.

The conversation between Nick and Suresh was part of a panel titled “Digital Innovation – Exploring the Next Frontier” at the BITS School of Management’s BEACON Festival of Ideas, organized in collaboration with the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development.

[1] https://www.npci.org.in/what-we-do/upi/product-overview