Urbanisation in Africa represents a huge opportunity for the continent. The increased concentration of people in urban spaces is good for workers and businesses alike, since economic density will bring gains in productivity and quality of life.

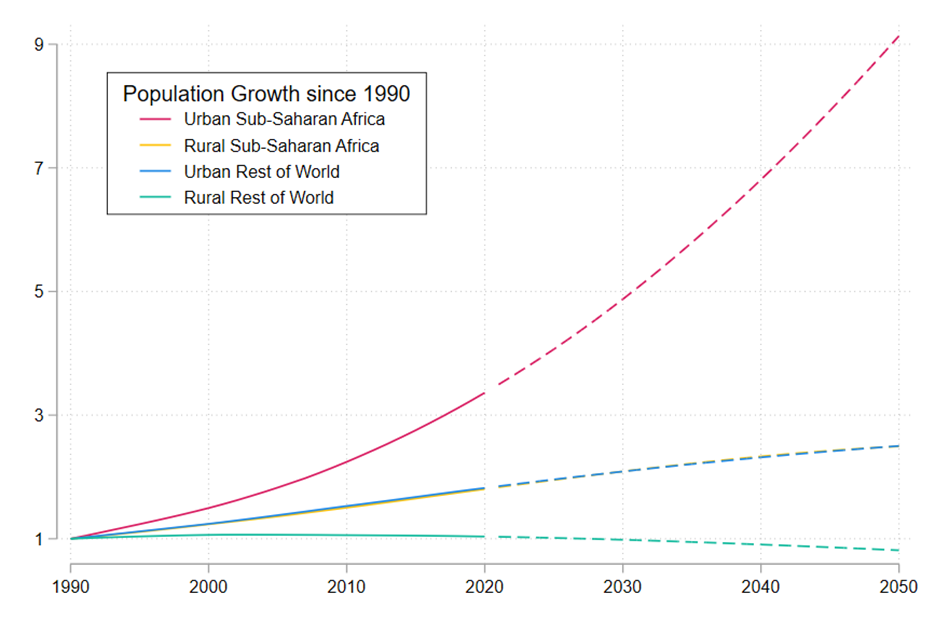

There are 500 million people living in African cities with another 700 million expected by 2050. This population growth is much faster than urban areas around the rest of the world and is significantly outpacing rural regions on the continent.

The fast growth of cities in Africa means a surging demand for urban housing. How will the land market in these cities respond to this? What policies can improve the way the market functions? How can low-capacity governments implement these policies in practice? This short blog series will engage with these questions and hopefully inspire further research and interest from practitioners in this increasingly important area of real estate and urban economics.

The opportunity of urbanisation

Urbanisation in Africa represents a huge opportunity for the continent. The increased concentration of people in urban spaces is good for workers and businesses alike, since economic density has the potential to bring gains in productivity and quality of life. Across Africa, a doubling in population density increases net income by about 31% and hourly wages by 5%.[1] The urban wage premium suggests that workers in cities are more productive since firms are willing to pay more for their labour. Other social outcomes, such as health and education are also better in cities than outside them.[2] Further evidence of the increased social benefits of greater urban density is the attendant appreciation in land value. For example, a typical plot of land in Nairobi fetches a price 250-300% higher than it did in 2011.[3]

African cities are exciting places with much potential. However, there are also downsides to urban density that can be particularly acute in developing countries. Understanding these issues and how they can be mitigated is key for African cities to flourish.

Challenges in the real-estate markets of Africa

There are at least two important institutional features in understanding failures in the land markets of African cities: a lack of property rights and minimal urban planning. Density is good for productivity and quality of life only if properly planned and managed. Property rights are fundamental for private investment, which in turn is important for ensuring that the housing stock responds to demand. Without formal land titles, private investment and trade in land is at risk. In Tanzania, for instance, there are anecdotes of the same plot being fraudulently sold to 30 different individuals. [4] Mortgage markets also struggle without title-backed collateral. Customary land-tenure systems, which can work well in the rural hinterland, cannot accommodate the high stakes and complex land markets of large, modern cities. Government investment and planning is also important. Public services ensure that density leads to connectivity (e.g. roads and public transport) and mitigates hazards to health (e.g. piped water and sewerage). On the other hand, laissez-faire urban development leads to encroachment of land and crowding of services. Further, in cases where urban planning is enforced it can be based on misguided colonial policy; for example, the building regulations in Nairobi once required roofs to withstand six inches of snow since the bylaws were simply copied from those of Blackburn, England.[5] These issues on planning and property rights in African cities will be explored further in the second post of this blog series.

Land and housing policy responses

What appropriate policies can improve the real-estate markets of African cities? Slums proliferate in urban Africa. These areas are characterised by both low public and private capital investment. Various policy responses are proposed to provide neighbourhoods with higher-quality public and private infrastructure. These can differ greatly in terms of cost: on the high end is state-provided housing, such as in Ethiopia[6]; on the low end is pre-emptive demarcation of roads, plots and drainage, such as in Tanzania[7]. Potentially the most common policy response, slum upgrading, lies somewhere in between. It is important that policy solutions are cost-effective; however, they also need to be significant enough to overcome the underlying failures of the land market they are trying to address. The third post of this blog series will discuss evidence on housing policies that work and those that don’t.

Raising capacity of local governments

It is one thing to come up with policy and another to implement it. This is a particularly difficult task for city governments in Africa, which often have low capacity. Capacity can be low, both in a productive sense and in an extractive sense. Low productive capacity can stem from poor incentives in government; for instance, ethnic favouritism has been found to distort rental markets in Kenya. In informal settlements, landlords who are of the same ethnic group as local chiefs receive higher rents from tenants and invest less in housing.[8] Even if a government has high productive capacity, it needs funding, so extractive capacity is also important. However, local African governments often struggle to raise funds. Property-tax collection is extremely low in many contexts and informality limits rents from business licenses and sales taxes. The fourth and final post in this blog series will discuss ways in which city governments in Africa can raise their capacity.

Background reading

[1] Urbanization in the developing world: Too early or to slow? Henderson and Turner, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2020.

[2] Do urban wage premia reflect lower amenities? Evidence from Africa. Gollin, Kirchberger, and Lagakos, Journal of Urban Economics, 2021.

[3] Land Price Index Quarter One Report 2021. Hass Consult LTD.

[4] Urban land governance in Dar es Salaam: Actors, processes and ownership documentation. Wolff, Kuch and Chipman, 2018.

[5] Reforming Urban Laws in Africa: A Practical Guide.

[6] The demand for government housing: Evidence from lotteries for 200,000 homes in Ethiopia. Simon Franklin, 2019.

[7] Planning Ahead for Better Neighborhoods: Long Run Evidence from Tanzania. Michaels, Nigmatulina, Rauch, Regan, Baruah, and Dahlstrand, Journal of Political Economy, 2021.

[8] There Is No Free House: Ethnic Patronage in a Kenyan Slum. Marx, Stoker, and Suri, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2020.

Harnessing the potential of urbanisation in Africa is a short series exploring the exponential growth of African cities and the challenges and opportunities this presents for the housing market and its impact on productivity and quality of life. Over the next few months, we will release several articles covering (1) the existing issues facing the efficient development of African cities, (2) policy options to mitigate these issues, and (3) how we can improve state capacity to allow African governments to implement new policies. This series aims to inspire further research and interest from practitioners in this increasingly important area of real estate and urban economics.

Tanner Regan is a Research Fellow in Economics at London Business School, focusing on the economics of housing, land tenure, urban planning, and property tax in developing country cities. He holds a PhD from the London School of Economics and MA and BSc degrees from the University of Toronto. He is affiliated with the Centre for Economic Performance and the International Growth Centre at the LSE.