The final session of the Tax Bootcamp 2024 at London Business School was focussed on two research papers, centred around tax and ESG in different geographical regions including developing countries. Each was presented by one of the researchers, discussed by an independent academic, and assessed for policy implications by a third party.

This article is the third in a three-part series. Find out more about parts one and two of the Bootcamp now: ‘Tax Strategies and the Technological Revolution: Accounting for AI‘; ‘Taxes for Climate Action Across the World‘.

Motivating ESG Activities through Contracts, Taxes and Disclosure Regulation

Presenter: Amoray Riggs-Cragun (Assistant Professor of Accounting at Chicago Booth)

Discussant: Henry Friedman (Associate Professor of Accounting at UCLA)

Policy Impulse: Gaizka Ormazabal (Grupo Santander Chair of Financial Institutions and Corporate Governance at IESE Business School)

Professor Riggs-Cragun began by presenting the theoretical research paper, ‘Motivating ESG Activities Through Contracts, Taxes and Disclosure Regulation’ (Jonathan Bonham and Amoray Riggs-Cragun, 2022). Using a model where firm managers can influence the entire distribution over financial and ESG outcomes, the paper examines how ESG activities can be motivated through contracts, taxes and disclosure regulation. It shows that ESG-performance-based shares incentivise managers to engage in green innovation, i.e. to increase the correlation between financial and ESG outcomes. While executive compensation contracts can motivate changes in a firm’s ESG activities, these changes are limited by how much shareholders value ESG. Taxes can align shareholder objectives more closely with societal objectives, but can have unintended consequences. Disclosure regulation can empower markets to self-discipline by providing information about firms’ ESG technologies, as this enables powerful ESG-conscious firms to compete against brown firms and cooperate with green firms. However, disclosure regulation can hurt ESG outcomes if powerful firms do not value ESG, and it has little effect when market power is disperse.

Professor Friedman argued that the paper is particularly interesting because it presents a lot of information about how people can make ESG outcomes profitable. This is crucial to achieving change more widely. He added the caveat that, given the nature of the paper as based on mathematical models with a necessary set of assumptions, the extent to which the model can be applied to the real world is unclear. He added a set of questions and extensions: first, the paper might consider that taxes cause ESG and performance to interact. Green production tax credits, for instance. Can managers be taxed directly? If so, this would change their preferred distributions. Can tax rules change measurement and reporting of certain performance measures? For instance, CBAM changes disclosures. And finally, what role does book-tax conformity play?

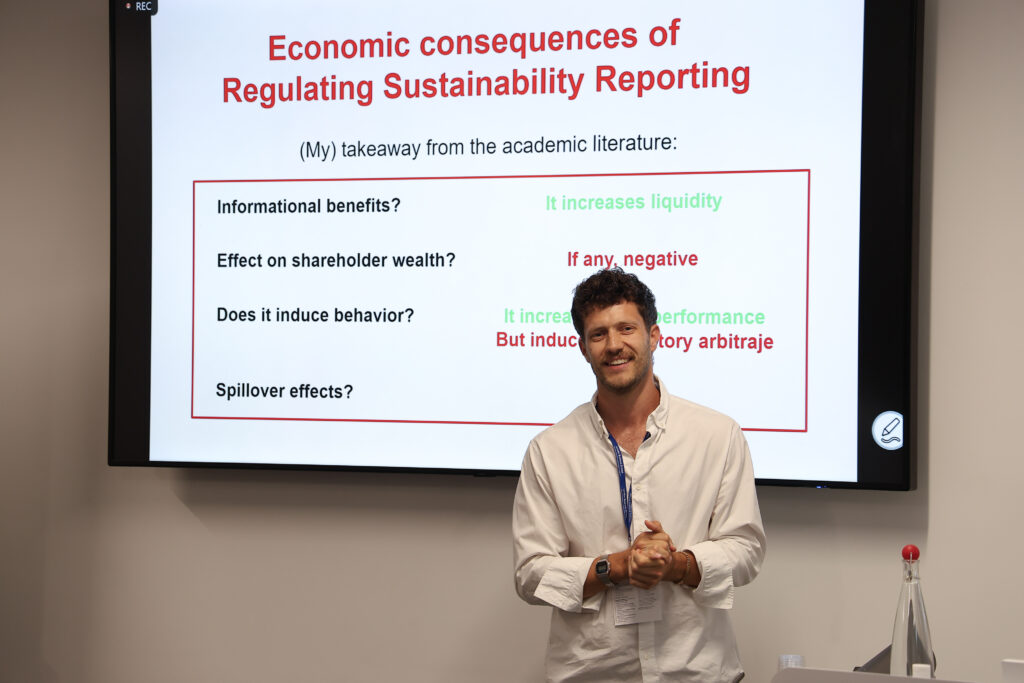

Gaizka followed with a presentation on ‘Regulating Sustainability Reporting: the empirical perspective’. He began by outlining some of the ESG regulation around reporting, such as the 2021 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) Proposal in Europe, and the ISSB internationally. He asked the deceptively simple question, ‘Do we need mandatory ESG disclosure?’ Demand for ESG information from PRI Signatories have increased, but so too has the voluntary supply of ESG information, so it could be argued that mandatory disclosure is less necessary than in the past due to cultural changes. Yet, voluntary disclosure is still not more than 18% internationally, and very few companies disclose on all 11 ESG points, so mandatory disclosure can still help to shed light on new areas. Gaizka added that there are a range of welfare effects of ESG mandatory disclosure, such as improving company credibility. But there are some negative effects. One study found that, when mandatory disclosures were enforced, stakeholder wealth was about 1% lower than a control group. Alonso, Jacob, Ormazabal, Ranay (2024) found that CBAM had a negative overall effect on international stock markets, particularly in Europe. There are also some spillover effects – Bonetti, En, Kadach, Ormazabal (2024) found that clients push firms to disclose on ESG, which could prove to be more effective than centralised measures.

Emission Taxes and Firms’ Pollution and Technological Change – the Swedish Experience

Presenter: Christian Thomann, Associate Professor of Finance at Royal Institute of Technology and Researcher at the Swedish House of Finance

Discussant: Martin Jacob, Professor of Accounting and Control at IESE Business School

Policy Impulse: Gilbert E. Metcalf, Professor of Economics Emeritus at Tufts University and a Visiting Professor at the MIT Sloan School, Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (CEEPR) and NBER

‘Does carbon taxing reduce emissions?’ This was the question at the heart of the paper presented by Professor Thomann. The paper looked at the relationship between carbon taxes and carbon emissions in Sweden, which started taxing CO2 emissions in 1991 and has the world’s highest carbon tax. ‘The basic idea,’ he suggested, ‘is that firms will invest in abatement as long as carbon tax savings from reducing a unit of CO2 are less than the cost of reducing one unit of CO2.’ 80% of Sweden’s CO2 emissions come from ‘dirty firms’ (high emitters) in the manufacturing sector, such as steel and cement refineries etc. They found that a 1% increase in marginal tax cost leads to 2% decrease in emission intensity. However, it takes time for firms to reduce emission intensities, and often takes up to three years. It is very difficult to get rid of emissions if you are in dirtiest sectors, and access to capital becomes vital for firms in sectors with highest emission intensities. Big emitters with no access to finance do not change their emissions, but big emitters with access to finance can reduce emissions. Thomann turned to a second, ongoing project, ‘Climate Policy and Firm Efficiency: Lessons From the Trucking Industry’ (Martinsson, Stromberg, Thomann), which finds that a 10% increase in tax inclusive fuel cost leads to 4% fewer Kms travelled by a truck, so a marginal impact on CO2 emissions.

Professor Jacob summarised by stating that environmental taxes foster innovation and R&D investments, and carbon taxes are successful in curbing emissions. His discussion points centred around the empirical evidence involved in the research, and avenues for future exploration. Regarding the former, he drew attention to other emissions such as NOx and Sox that are important when we talk about pollution, not just CO2. He also raised that reducing the pollution by making the polluter pay may cost jobs, could pass the tax burden to suppliers or customers, and could mean shifting activities to other countries, or ‘carbon leakage’. Jacob further pointed out different evidence from Spain when ESG taxes were studied. In Spain, the sulphur tax had very little impact beyond the general trend of reduction. There are key differences between Sweden and Spain – Sweden is much wealthier, for instance. The average income in Sweden is 63.5k USD, but almost half in Spain at 32k USD. Government debt in Sweden is 32% of their GDP, compared to 112% in Spain. So, what may work in Sweden might work in other Nordic countries. But can it work outside of Sweden generally? We don’t know, and future research is required.

About the organisers

Marcel Olbert is an Assistant Professor of Accounting at London Business School. Named as one of the 2024 Poets & Quants Best 40-Under-40 MBA Professors, his research interests focus on the real effects of corporate taxation and disclosure regulation – examining how multinational businesses respond to incentives that stem from their regulatory and macroeconomic environment. His broad range of experience includes investment banking within the M&A advisory group of JP Morgan London, strategy consulting with Roland Berger and international tax and private equity with PwC and Flick Gocke Schaumburg. Marcel also serves as an Associate Editor at the European Accounting Review. His work has been accepted for publication in The Accounting Review, the Journal of Accounting and Economics, the Journal of Accounting Research, and the Review of Financial Studies. His current research on tax reforms and multinational firm investment as well as on carbon taxes and carbon leakage in developing countries is featured by the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development. Marcel is seeking applications for professional research assistantships.

Rebecca Lester is an Associate Professor of Accounting and one of three inaugural Botha-Chan Faculty Scholars at Stanford Graduate School of Business. She is also a Research Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and at the Hoover Institution. Her research studies how tax policies affect corporate investment and employment decisions. In particular, she examines the role of reporting incentives, disclosure regimes, and information frictions in facilitating or altering the effectiveness of cross-border, federal, and local tax incentives. Her recent work explores national-level tax benefits, such as U.S. manufacturing tax incentives, European intellectual property tax regimes, and tax loss offsets. Other work examines state, local, and neighborhood-level incentives, including firm-specific tax incentives and the recent Opportunity Zones tax incentive. Professor Lester received her PhD in accounting from the MIT Sloan School of Management, and she has a BA and a Masters of Accountancy from the University of Tennessee. Prior to her studies at MIT, she worked for eight years at Deloitte in Chicago, including five years in the M&A Transaction Services practice.

The Tax Bootcamp 2024 would not have been possible without the generous support of the LBS Knowledge Exchange Fund, which gathers the expertise in learning from across the School and takes a view on prescient topics and offer advice on the most effective approaches.