This is the first article of a 3-part series on informal entrepreneurship in emerging markets, based on empirical research conducted in the township of Alexandra in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Elizabeth Mogale* (not her real name), a 48-year old mother of four, grills chickens on the pavement of 12th avenue in Alexandra, one of Johannesburg’s most densely populated townships, better known as “Alex”. Much of her business comes from commuters who are on their way to or from work. Many of her customers are regulars. She insists on sourcing her chicken from quality suppliers, because her clients won’t settle for less. The chicken is indeed delicious, and commuters flock to her plastic chairs and table on the pavement rather than to the KFC outlet a few blocks up the road. Elizabeth, who runs a tight ship, employs 3 people on a full time basis and owns a bakkie (pick-up truck). On average, each of them take home around R 1,200 per month. Not much by any standard, but it’s an income that goes some way towards covering rent, food, some basics, and perhaps a few dozen rand per month to save towards a TV, a micro-wave, or repairing a leaky roof.

While reliable data is hard to come by, there are an estimated 2.6 million micro-businesses in South Africa (defined as business employing 5 people or less)[1]. As is the case in most developing economies around the world, many entrepreneurs in South Africa thrive in the informal economy and have no particular incentive to formalize, mainly because the hassle factor often outstrips the benefits of going formal. For some, this will always be the case. However, for others, formalizing could mean easier access to credit, the ability to enter into recognized contractual relationships, secure property, distinguish between personal assets and business operations, and benefit from the relative protection offered by limited liability. Such benefits would help secure many businesses currently operating as survivalist ventures, and perhaps foster an entrepreneurial class.

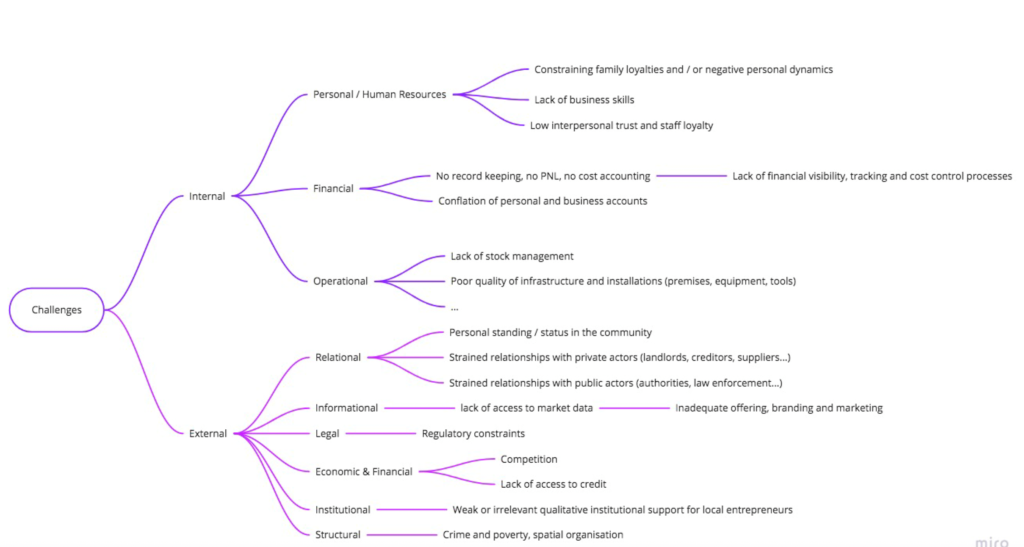

Based on qualitative data collected over 8 years, Reciprocity and the Wheeler Institute have attempted to map the challenges and obstacles that entrepreneurs such as Elizabeth face on a daily basis. These challenges turn out to be remarkably similar across the range of micro-businesses that can be found in Alex, from corner shops (locally known as “spazas”) to hair salons, street food vendors, cell phone repair stalls, micro-bakeries, internet cafés and a myriad of other small businesses catering to the needs of the population.

Individual entrepreneurial ecosystems may indeed vary vastly from one place to another, but micro-businesses in emerging economies face remarkably similar sets of challenges around the world. They are both internal challenges, linked to the individual entrepreneur and their business, and external ones, linked to the broader environment they operate within. Alex, possibly one of the most densely populated few square kilometres on earth, is a concentrate of these challenges. Learning from Alex can arguably help to understand the typical operating environments of millions of small businesses around the world. We summarise the challenges for you in the below diagram before sharing further detail below.

Start with the internal challenges. We classified these into three categories:

- People-related: These relate to the business owner herself, her household and family, as well as the surrounding social fabric. One particularly important dynamic, often observed in Alex, is that high poverty levels, combined with scarce employment opportunities, put a lot of pressure on anyone with a regular income to provide for relatives or dependents who aren’t earning a regular income. There might also be pressure on the entrepreneur to employ people who they might not be able to afford or need, because of family loyalty and expectations. Such social expectations are common and can sometimes (though not always) translate into negative interpersonal dynamics that affect the businesses’ prospects.

- Operational: In a cramped, very densely populated township like Alex, space comes at a premium. There may often be overlap between living quarters and business premises, or between business premises and public spaces such as pavements or streets. In many instances, buildings are poorly maintained, and it may not be clear who owns the premises and is responsible for maintenance.

- Financial: Typically, entrepreneurs operating in this environment may not be able to keep any records to track income and expenses. There is rarely any clear distinction between business money and personal money. Income from business activities goes directly into household or personal accounts. While there are very rational reasons for this, the lack of record keeping often means that entrepreneurs lack the information they need to make decisions on which products to stock, which ones to ditch, and what their margins are.

On top of these internal hurdles, small business owners also face a number of external challenges, including:

- Relationships: Like entrepreneurs anywhere, business owners in a township need to carefully manage their relationships with clients and suppliers, but also with the community in which they live and work, as well as public and private stakeholders they interact with. In the constrained, highly competitive environment of a township, agreements with landlords, creditors and suppliers, which are often verbal, can be precarious and subject to sudden change. Interactions with public actors, for example law enforcement, can also be subject to challenges not often encountered by formal businesses outside the township, such as direct demands for bribes or protection money. Within the surrounding community, the entrepreneur’s identity and origins can have a positive or negative impact on how they are perceived by others, especially in places like Alex, which is a remarkably diverse melting pot of people from all over Southern Africa and beyond.

- Lack of access to information: Business owners rarely have enough time to do research or resources to spend on data. This is exemplified by a substantial number of entrepreneurs who do not have a clear idea of available institutional support, or where to go to benefit from this support. Typically, market information on customer trends and changes may not be accessible, leaving business owners to rely on empirical observation and instinct to respond to changes in the market.

- Regulatory environment: South Africa’s formal regulatory framework does not reflect the needs and realities of doing business in Alex or any other township environment. Compliance with the existing legal framework, such as registering a business, or filing annual accounts and tax returns, make little sense in an environment in which agreements are often verbal, transactions are in cash, and the cost of compliance does not justify the hassle and paperwork. However, registration is a prerequisite to access almost any resource, including support from public sector agencies supposedly mandated to support township businesses, and access to basic banking services. This mismatch between the realities on the ground and the existing requirements is one of the biggest external challenges faced by entrepreneurs.

- Economic and financial: Linked to the challenges of the regulatory environment, access to formal credit, for example, is in practice restricted by regulatory constraints. Formal lenders and credit providers (including public sector agencies supposed to assist entrepreneurs) as a rule extend credit only to registered businesses. This leaves a large proportion of business owners either unable to access productive credit, or reliant on informal options, which may be more expensive or risky for them, such as loan sharks, informal savings groups or family and friends.

- Institutional support: On paper, the available support system for entrepreneurs is encouraging. A number of government agencies, as well as private sector organisations and foundations provide small businesses with financial and non-financial support. In practice however, small business owners from Alex and other townships struggle immensely to navigate the landscape of organisations and, more importantly, to meet eligibility criteria – with bank statements, registrations documents and accurate record keeping – to be even considered for support

- Structural: As if the above list of obstacles were not enough, business owners in Alex bear the brunt of some of South Africa’s deep-seated structural issues that are well beyond their control. High crime levels, as well as spatial constraints that are directly inherited from the apartheid era. The population densities are far beyond what existing housing and municipal infrastructure was designed to accommodate, Alex’s narrow streets are now clogged with paralysing traffic, and there is constant competition between living and working space.

Considering this landscape of challenges, it is all the more remarkable that a place like Alex produces so many businesses. However, if the disconnect between the offering in the ecosystem and the needs of business owners like the profile of Elizabeth Mogale could be better bridged, how much economic growth could be unlocked ? How many jobs could be created and secured ? Our next article on Alex will explore this question.

LBS students have been collaborating with micro-entrepreneurs in Alexandra Township (‘Alex’) in Johannesburg for ten years, with over 700 MBA students helping 150 entrepreneurs respond to business challenges. This engagement with the Alex business ecosystem is delivered through a partnership with Nicolas Pascarel and Pierre Coetzer of Reciprocity, and Piki Phasha from Leborogo. Members of the Wheeler Institute were involved in establishing and delivering this engagement (Global Experience). The Wheeler Institute also collaborates with Reciprocity on identifying and implementing ways to best support the development of a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Reciprocity is a Cape Town and Tunis based consultancy looking to unlock the potential of business as an agent of economic transformation, and maximize the positive socioeconomic footprint of business in low income segments.

Pierre Coetzer and Nicolas Pascarel are the founding associates of Reciprocity.

[1] As quoted by the Centre for Development Enterprise, 2021. “What role can small and microbusinesses play in achieving inclusive growth”?

Ayorinde Ezekiel Ezekiel

Norma Migone