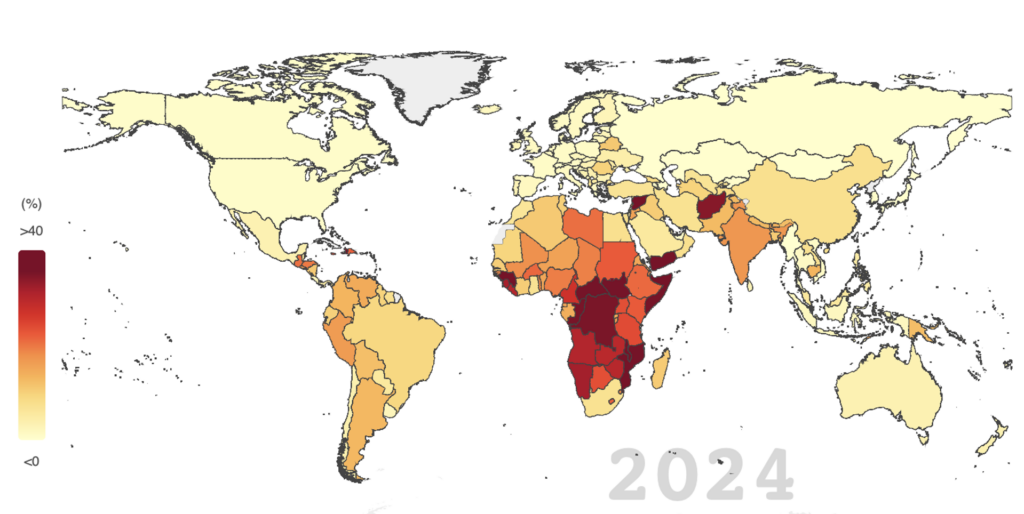

The world is facing a severe food crisis. The latest State of Food Security and Nutrition report stated that around 2.4 billion people across the planet faced moderate to severe food insecurity in 2022, including 900 million with severe food insecurity.1 Although the global hunger rates have stabilised since the COVID-19 crisis, they remain significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels. There are increasing concerns that we are distant from achieving the Sustainable Development Goal number two: Zero Hunger. Key challenges for progress include global conflict, climate change, and economic instability. Furthermore, with the population expected to reach 10 billion by 2050, the UN estimates a need for a 60% increase in food production to avoid further food insecurity that would pronominally impact developing countries.

The World Economic Forum (2024) highlights Latin America as a strategic player in addressing global food scarcity. The report points out the region’s control of 15% of the world’s land area, its geopolitically neutral stance, and a substantial labour force of over 300 million as key factors that make the region an agro-industrial superpower for global exports of fruits and vegetables.2 Despite this, Latin America has not yet succeeded in guaranteeing food security for its population. In 2022, 37.5% of Latin Americans and Caribbeans faced food insecurity—significantly higher than the global average of 29.6%. Additionally, in 2021, the region showed the world’s highest cost of a healthy diet3. Income inequalities and inadequate food expenditure, where less developed areas struggle with subsistence agriculture, have significantly influenced the food crisis in Latin America. Economic recessions and waves of violence have exacerbated the problem, especially in Central American countries. Moreover, climate change is becoming a widespread threat to agricultural production. As Mario Lubetkin (FAO Assistant Director-General) points out, “The hunger figures in our region continue to be worrying. We see how we are moving further and further away from meeting the 2030 agenda, and we have not yet managed to improve the figures before the crisis unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic”4.

From an economic perspective, Latin America’s food security is closely linked to global trade dynamics, as local agricultural strategies and policies are heavily swayed by external demands (Espinosa-Cristia et al. 2019).5 The region exports 25% of its agricultural output (vs. Asia’s 6%), primarily to major markets like the US, EU, and China, with Mexico alone sending over 60% of its exports to the US. This export focus, coupled with the phenomenon of “land-grabbing,” where foreign entities acquire local land for food production destined for their markets, makes the region closely linked to international commodity markets and highly sensitive to changes in global prices (IFPRI, 20236; Zimmerman, 20247).

The prioritisation of exports results in two additional challenges. On the one hand, it leads to a specialization in low-value-added foods in developing countries (Espinosa-Cristia et al., 2019). On the other hand, it adversely impacts small-scale producers and farmers, who make up 57%-77% of the agricultural workforce and produce between 27% and 67% of the region’s food. Despite their vital role in maintaining food security and biodiversity, these producers confront significant economic hardships and food insecurity (Chicoma, 2023)8.

With this, there is a question of the role of Latin America in the global food crisis. While addressing the crisis requires a collaborative approach, this must be done in a balanced way that safeguards the region’s own food security. Strategies suggested by different actors range from crafting new local-focused policies to including new technologies in the supply- chain. From the policy side, some authors suggest involving smallholder farmers and artisanal fishers in decision-making processes and crafting policies to solve problems of small-scale production and commercialization (Chicoma, 2023; Yunez-Naude, 20159). The Inter-American Development Bank advocates for creating climate-resilient agriculture and policy incentives that promote the production of nutritious foods and make healthy diets more accessible10. From the technological side, Espinosa-Cristia et al (2019) calls for the use of data science and blockchain to streamline operations and bridge rural-urban divides. Additionally, they highlight mobile technology to empower rural producers with crucial market and agricultural information.

As Latin America stands at the forefront of the global food crisis, it is crucial to harmonise its role as a major agricultural exporter with its internal challenges. The region’s strategic response can include enhancing local food systems and integrating small-scale producers more deeply into economic planning and technological advancements. By aligning international trade dynamics with sustainable local practices, Latin America could move towards a more secure agricultural future.

Sources

[1] https://www.fao.org/publications/home/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world/en

[2] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/latin-america-solution-food-insecurity/

[3] https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en?details=CC8514EN

[4]https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/new-un-report-43-million-people-suffer-from-hunger-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean

[5] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pa.1999

[6] https://www.ifpri.org/blog/global-food-policy-report-2023-latin-america-launch-policies-build-resilienceshocks#:~:text=LAC’s%20food%20systems%20challenges&text=The%20region’s%20economy%20is%20closely,countries%20with%20strong%20economic%20performance

[7] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1866802X231223754

[8] https://foodtank.com/news/2023/02/latin-americas-food-paradox/

[9]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283837390_Agriculture_Food_Security_and_Livelihoods_of_the_Mexican_Population_Under_Market-Oriented_Reforms

[10] https://www.iadb.org/en/news/food-security-latin-america-and-caribbean#:~:text=Solutions%20Proposed%20by%20the%20IDB,indigenous%20peoples%20and%20Afro%2Ddescendants.

Student voice

The Wheeler Institute for Business and Development is seeking to understand, illuminate and offer solutions to the challenges faced by the developing world, with an aim to identify the role of business in addressing these challenges and a focus on the implications and actions for those in developing countries. In support of our students, we approach this blog section as a reflective platform and a space where individuals can generate debate as long-term agents of positive change. This article is solely authored by a student and reflects their individual research, opinion and point of view and is not based on research led or supported by the Wheeler Institute.

About the author

Juliana Escobar Díaz (LBS MBA 2025) is an Outreach and Communications Intern at the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development. Prior to joining London Business School, Juliana spent four years at McKinsey & Company as a Location and Business Analyst, based in Bogotá. She has a keen interest in business for impact and business as a force for good.