This week, I visited the Co-op on Baker Street, close to the School’s Sussex Place Campus, looking for some instant iced coffee. My eyes were drawn to Co-op’s branded Fairtrade Iced Coffee. The blue, green and black logo seemed familiar. I had stumbled upon it a few years ago as I was searching for a new brand of instant coffee powder to purchase.

In this article, I introduce the concept of Fairtrade and explore its relevance today.

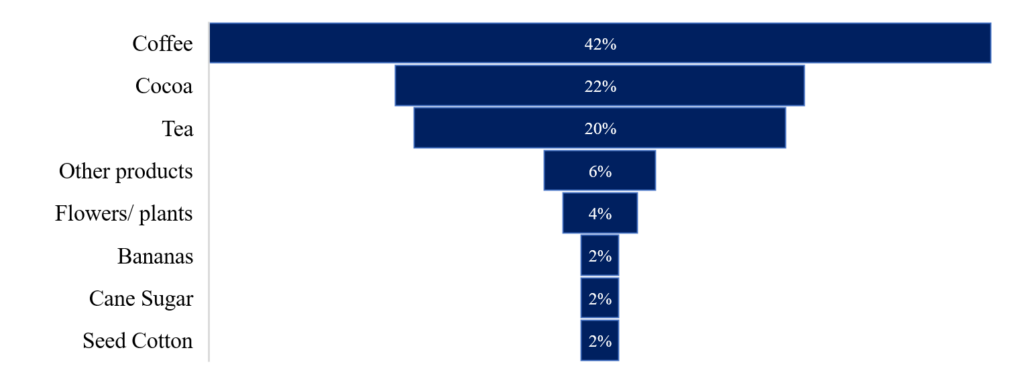

Fairtrade is a consumer product certification that implies a certain quality standard has been met in the production and supply of that product (or its ingredients). This certification is a global recognition to complying producers and traders. Overall, empowering producers such as farmers to attain more control over their livelihood while also promoting equitable trade is the underlying mission of the global non-profit Fairtrade International. Its local chapters are spread across Africa, Asia Pacific, the Caribbean, Latin America, and the Middle East. In 2019, coffee and cocoa comprised over 60% of total Fairtrade sales (see below, Monitoring the scope and benefits of Fairtrade. 12th edn).

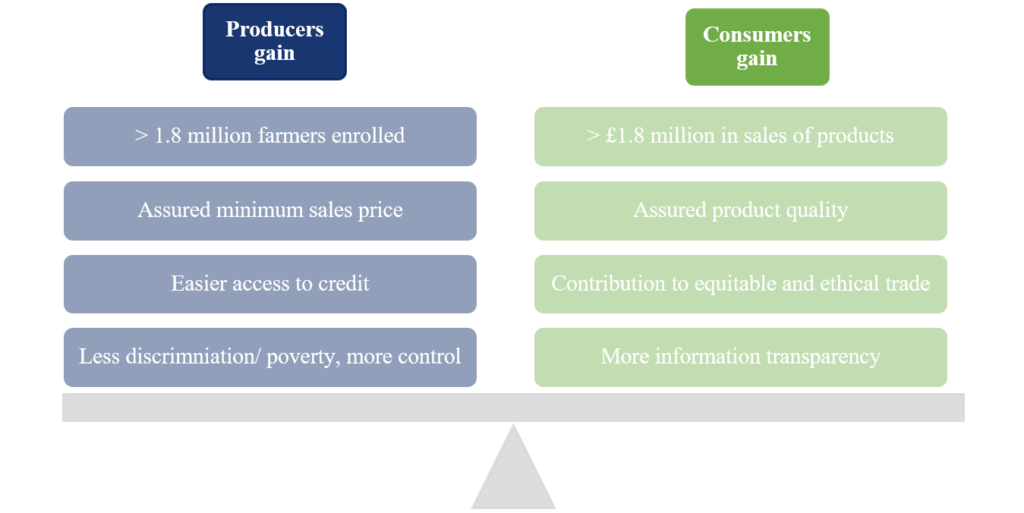

That a trade system can benefit and be just to both the producers and the consumers seems utopian in current capitalist environments. However, this is the precipice upon which the Fairtrade mission was created. The figure below highlights the benefits that accrue under a fair trade economy.

Assessing the ‘Fair’ness – an example of Fairtrade coffee

Let’s understand how the process works.

Farmers that produce coffee will enlist themselves in local cooperatives around the world. It is then Fairtrade’s responsibility to assess the quality control of these cooperatives and award them with the FAIRTRADE mark if they comply with the standards. Once awarded, these are Fairtrade coffee associations. Currently, there are 23 such associations across countries in East Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. Fairtrade then assembles companies that would buy coffee from these coffee associations at a fixed price – which is usually set to minimize any losses for the farmers on a gross profit or contribution margin basis. In the UK, buyers of Fairtrade coffee include Asda, Co-op, Joe & the Juice, John Lewis, Lidl, Marks & Spencer and Pizza Express.

The minimum price for Fairtrade arabica coffee is US$1.40 per kg, or US$ 1.70 per kg if the produce is organic. However, a buyer like Co-op will in fact pay US$ 1.60 per kg (or US$ 1.90 per kg for organic produce). The difference is the Fairtrade Premium which Co-op must pay. About 25% of this premium is allocated to optimizing the coffee production, and the remaining is used for community development measures, at the discretion of the local coffee association.

Now, let’s see the potential issues that could arise from this process.

The fact that there is a ‘premium’ that Fairtrade coffee buyers need to pay is problematic in today’s economic climate. There is a two-fold scepticism. With inflationary pressures, companies are struggling to cover their own operating cost, questioning the premise that they are openly made to pay a premium that is partially unrelated to production. Additionally, accounting for a mandate on the premium, there is a lack of control by the premium payers over how it is used. Both these levers are paving the way for a movement of companies taking sustainable and equitable manufacturing practices in-house, thereby eliminating the need for the existence of Fairtrade International.

Another issue lies with the composition of the farmer cooperatives. While the Fairtrade farmer and other members in the cooperative are guaranteed ‘fair’ or ‘market’ prices for their products, there is no such equitable proposition for other workers on the plantation that might be involved in smaller tasks. This is counterfactual to the mission and often sparks debate on the superficiality of the Fairtrade guarantee.

Finally, there is the question of product pricing, which determines whether consumers will even choose to buy a Fairtrade product. There are two possible consumers. The first consumer has an above-average level of awareness, is conscious about sustainable trade, and is willing to pay the necessary price. The second consumer is indifferent and likely to pick up the product that’s either reasonably priced or has recall value. Both consumers call for competitive pricing of Fairtrade products. If products are priced at a premium, the first consumer will only shop Fairtrade in exchange for high product quality. This is subjective and difficult to measure at an individual level. If the products are priced competitively, the second consumer might only shop Fairtrade if they are aware of the mission. Either way, pricing is a key lever that underpins the success of the Fairtrade model.

The future of Fairtrade

It is evident that Fairtrade has flaws. However, the ideas on which it is based are still relevant. To sustain the relevance, a few things need to change. It might seem compelling to be an armchair critique of Fairtrade’s fallacies. However, with increasing consumerism, there is also added responsibility on the consumer.

Consumers should first take advantage of local legislation that protects their rights. These laws and forums grant consumers access to transparent information and answers to any product-related queries they may have. As brands are using social media platforms to reach their target consumers, the consumers should also use these opportunities to engage with the brands they shop from. Competitive pressures have increased how seriously brands need to take consumer feedback, and this can go a long way in ensuring near-perfect information symmetry in consumer purchasing decisions. Consumer awareness is the critical forcing mechanism that will compel producers and manufactures to be off autopilot and stay attuned and committed to ‘Fair Trade’.

Devanshi Shah (MBA2024) worked for five years in economic and financial consulting in India and the UAE before coming to LBS. She has advised clients across industries including construction, oil and gas, retail, and real estate, on how to value monetary and other damages arising from legal disputes. She is passionate about inclusivity in finance and education, particularly that marginalized populations in developing countries should be a focus in policy decisions.

The Wheeler Institute is seeking to understand, illuminate and offer solutions to the challenges faced by the developing world, with an aim to identify the role of business in addressing these challenges and a focus on the implications and actions for those in developing countries. In support of our students, we approach this blog section as a reflective platform and a space where individuals can generate debate as long-term agents of positive change.