Unemployment and literacy – two themes that have been met with interest in public policy for decades. While the scrutiny is justified, what perhaps is needed is a nuanced lens to the relationship between the two. Particularly in a post-pandemic world, as businesses and economies navigate for survival with a shift in priorities, the spillover effects are important to note.

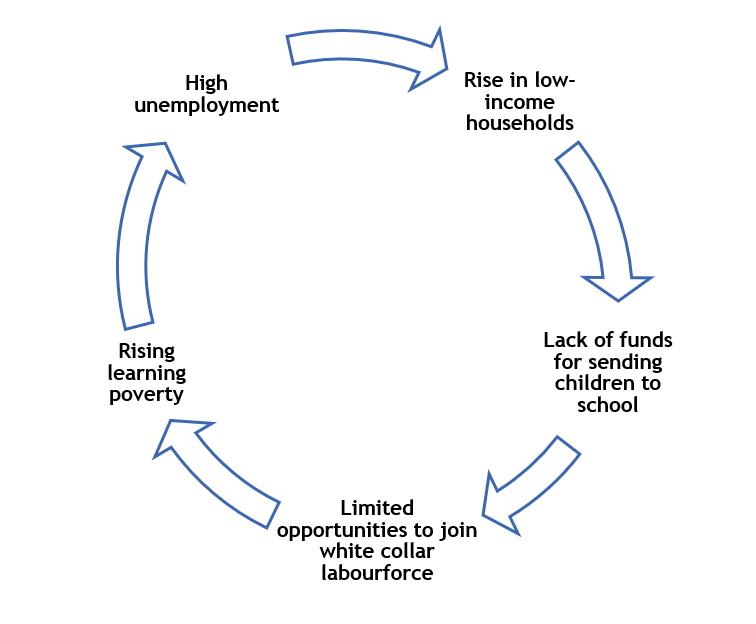

Let’s think about it: families living below poverty lines across the world (increased number due to COVID-19) — cannot afford education for their eligible children — these children lack preparedness for white-collar employment — economies and employers do not have access to quality talent — jobs are cut. This is a vicious cycle. Take a look below.

Flagging the starting point of this cycle is like solving the chicken-or-egg first riddle. However, the underlying rationale is straightforward – there is a direct relationship between inequality in education and inequality in employment. In this article, we take a deeper look into the former, learning poverty.

What is Learning Poverty?

Learning poverty is a measure of a child’s inability to meet minimum proficiency in reading, numeracy, and other skills at the primary school level. A country with high levels of learning poverty signals the failure of its educational system.

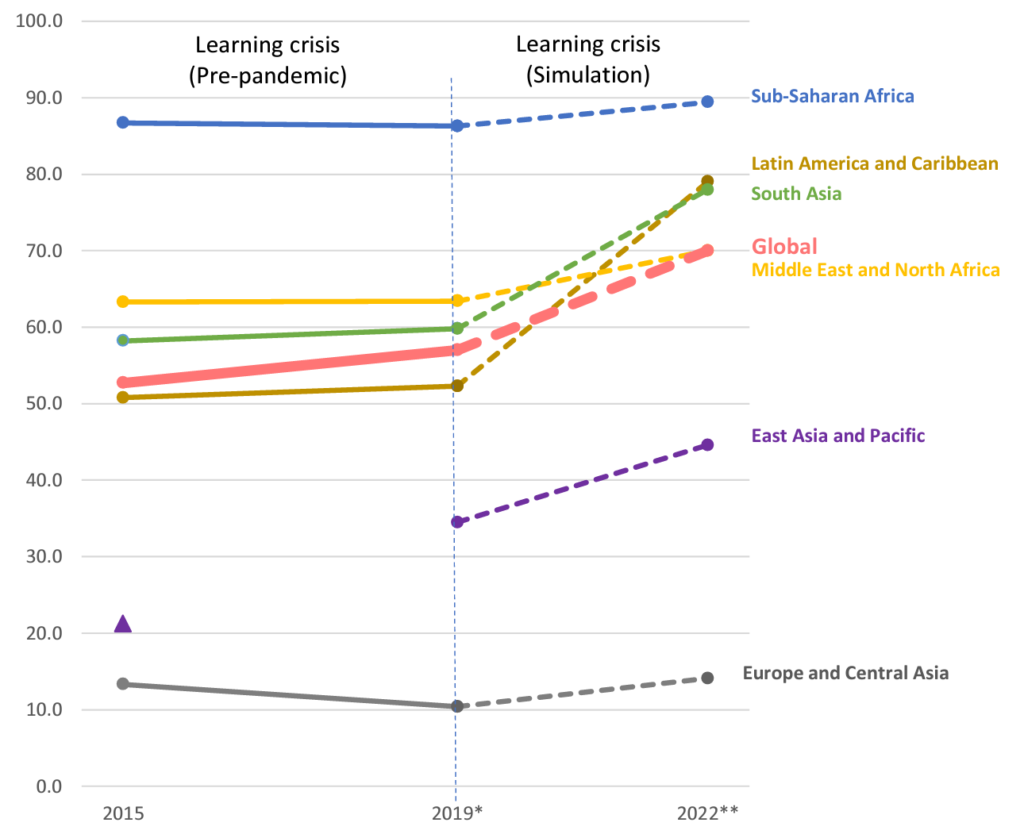

In 2019, UNESCO and the World Bank measured learning poverty at a global average of 53%. In other terms, 53% of the children enrolled in schools all over the world would not be able to read, write or calculate at the levels mandated in their regional schools by the age of 10 (or 12, in certain countries). Around the same time, global enrolment of children in primary schools stood at almost 90%. This shows that enrolling children in school was not yielding enough or expected outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic did not help. A global study estimated steep increases in learning poverty resulting from school closures during COVID‑19, especially in low and middle-income developing countries.

Why is this a problem now?

Consider the following two facts.

First, the World Bank publishes a Learning-Adjusted Years of School (LAYS) index that assesses a blend of the quality and quantity of education received by the youth of the respective country. Based on the most recently available data for 157 countries, just between 2017 and 2020, 42% of countries reported a decline in the LAYS at the aggregate level (considering both women and men).

Second, by 2025, it is estimated that 50% of the labour force will require re-skilling. This translates to one of two outcomes: first, people who stay in their current professions will observe a significant shift in skills needed to fulfill job responsibilities, or second, the current workforce will be unable to meet the demands of the shift in skills needed, and thus lose their jobs – to technology, or other skilled people.

There is an apparent and enormous gap between the two facts. Standards of global education are falling. However, the future of work is fast approaching. Catching up with the skills that employers will seek tomorrow means that education systems need to improve today.

What is the Call for Action?

Quality education for all is part of the UN SDG 4. Given the global significance, the UN and related entities have commenced major initiatives to address this. Following are some other recommendations calling for larger overhauls of the education system to bridge the gap between increasing learning poverty and the proximity of the future of work:

1. Skills and experience-based learning

The era of education focusing on only basic cognitive and analytical skills is behind us. The future of work will warrant an increased demand for creativity, resilience, and other softer skills. Curricula globally need to evolve to infuse holistic learning.

2. Higher government expenditure on digital learning and initiatives

COVID-19 exhibited the need to accelerate digital learning. Learning poverty is largely concentrated in low- and mid-income countries – where access to electronic devices is limited. Governments need to invest in technology systems and their integration with education systems.

3. Timely interventions

The rate at which technology and society are changing is increasing exponentially, calling for more frequent upgrades in learning systems. Consumers and education providers should act as responsive watchdogs to ensure that systems adapt to changing needs.

These measures serve as a minor impetus to what needs to be a larger shift in the outlook of education policy. While they cannot eliminate unemployment and solve the skill deficit entirely, they are steps towards forging a workforce that will be more prepared for systemic shocks arising from a changing world – whether a pandemic or technological evolution.

Devanshi Shah (MBA2024) worked for five years in economic and financial consulting in India and the UAE before coming to LBS. She has advised clients across industries including construction, oil and gas, retail, and real estate, on how to value monetary and other damages arising from legal disputes. She is passionate about inclusivity in finance and education, particularly that marginalized populations in developing countries should be a focus in policy decisions.

The Wheeler Institute is seeking to understand, illuminate and offer solutions to the challenges faced by the developing world, with an aim to identify the role of business in addressing these challenges and a focus on the implications and actions for those in developing countries. In support of our students, we approach this blog section as a reflective platform and a space where individuals can generate debate as long-term agents of positive change.