At the crossroads of history, where displacement and the repercussions of refugee flows intersect with economic, political, and social dynamics, the Refugees of the Mediterranean research project, led by Elias Papaioannou, Co-Academic Director of the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development and Professor of Economics at London Business School, and Stelios Michalopoulos, Eastman Professor of Economics at Brown University, aims to help understand questions on the political economy of displacement and refugee flows. Supported by the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development and the National Science Foundation (NSF) Major Grant, the research delves into the far-reaching consequences of Greece’s substantial refugee influx in the 1920s. By examining the multifaceted impacts of this historical displacement, it offers insights into education, entrepreneurship, occupational choices, voting patterns, culture, illuminating key aspects of the political economy of refugee flows.

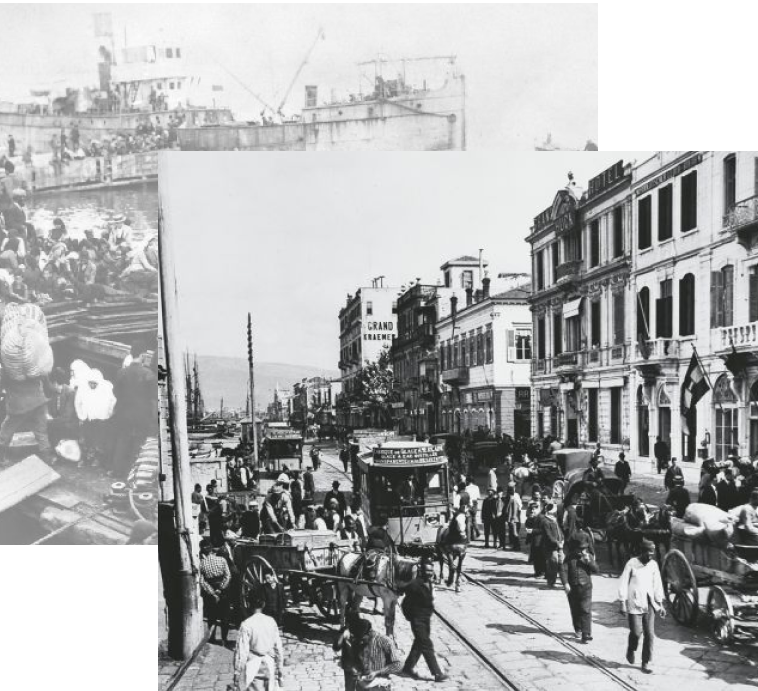

As part of the research project, Anatolia Imprints, an innovative digital database website, has been launched with the goal of illustrating the profound economic, political, and social effects of the wave of refugees that arrived in Greece during the 1920s, primarily from Asia Minor. The initiative employs cutting-edge technology and economic analysis to explore the consequences of this historical event that has defined modern Greece.

Anatolia Imprints involves digitizing and mapping data from the 1928 population census, which uniquely documents the origins and settlements of both refugees and natives across thousands of locations in Greece. Besides, the research team, which mainly consisted of dozens of young scholars at the University of Ioannina, digitized various catalog recording the households fleeing Asia Minor, Pontus, Cappadocia, and Eastern Thrace in the early 1920s and seeking refugee in Greece’s countryside and the big cities. This detailed information provides insights into the dispersion of refugees from specific areas in contemporary Turkey to various parts of Greece. Michalopoulos and Papaioannou, working with many colleagues, use the newly compiled data to tackle a series of questions on the short- and long-run effects of refugees in Greece’s economy and polity.

In the first paper, the researchers utilize microdata from population censuses conducted between 1971 and 2011 to examine the dynamics of education and employment sectors, internal and external migration, and living conditions, comparing refugee villages and small towns to nearby, comparable in the early 1920s settlements. Contrary to prevailing folk wisdom, the research challenges the notion that refugees had higher education levels. In contrast, illiteracy rates were higher for refugees settling in the countryside and Greece’s main cities. But the refugee villages, settlements, and small towns exhibit fast educational catch-up and record higher schooling rates within a generation, consistent with the uprootedness hypothesis. Furthermore, the ongoing research reveals that refugee communities were pivotal in transforming the Greek economy from agrarian to industrial and service-based. By working in textiles and manufacturing, refugees, especially women, contributed significantly to local industry in villages and cities. The research team (Nikolaos Benos, Stelios Michalopoulos, Elias Papaioannou, Seyhun Sakalli, Ellie Murard, and Stelios Karagiannis) attribute this rapid advancement to educational reforms and human capital investments resulting from the loss of physical assets. Finally, the research team uncovers evidence supporting the conjecture, popular across many refugee communities, that once a refugee/migrant, always a refugee/migrant. Specifically, there is clear-cut evidence that the first, second, and third generation of the forcibly displaced are more likely to migrate from Greece’s countryside to the main cities seeking opportunity. And Greeks from refugee villages and small towns are overwhelmingly more likely to migrate to Germany (and elsewhere) as Gastarbeiter in the 1950s and 1960s.

Secondly, Stelios Michalopoulos, Elias Papaioannou, and Vassilis Logothetis (University of Ioannina) examine the political behaviors of refugees, analyzing electoral rolls from different decades to uncover enduring differences between refugee and non-refugee neighborhoods. Refugees move to the left shortly after their forced settlement in Athens, Salonica, and Piraeus. And Refugee neighborhoods still vote left a century after the Exodus from Asia Minor. Surveys and opinion polls also indicate that Greeks identifying today with ancestors from Asia Minor, Pontus, Cappadocia, and Eastern Thrace have stronger redistribution preferences, lower trust to political institutions, and feel that society is unjust. These findings underline the lasting impact of historical events on political preferences and loyalties.

Third, Logothetis, Michalopoulos, and Papaioannou perform an innovative analysis of cultural evolution connecting it to forced displacement, applying machine learning techniques to extract the content of the universe of Greek songs since the late 19th century. The authors extract the content of Greek songs, distinguishing by the origin of the songwriter, the composer, and the first performer. While in the early 20th century, many Greek songs were about poverty, destitute living conditions, inequality, and conflict, as the economy developed, the themes changed, and over time, one observes more songs about love, joy, and pleasure. Refugee artists write and sing more than non-refugees about poverty, conditions in slums, and injustice, in line with their dire livings when they arrived, penniless in Greece, facing resentment from the locals. But as refugees accumulate human (and physical capital) the themes converge, telling of a link from economics to culture. Nonetheless, artists of refugee origin still discuss and sing songs on inequality, injustice, unfairness, grit, and perseverance, revealing a link between their ancestors past, their identity, and political preferences today.

Future plans include the publication of maps illustrating refugee settlements in Greek cities and machine learning application to identify likely refugee surnames, among others.

Anatolia Imprints provides a unique and comprehensive perspective on the long-term consequences of refugee influxes, shedding light on how past events continue to shape the social, economic, and political landscape of contemporary Greece. The project’s multidisciplinary approach and utilization of geospatial data, alongside machine learning techniques to extract the content of cultural output, serves as a model for future research endeavors, addressing gaps in historical knowledge and contributing to a deeper understanding of societal dynamics.

In today’s world, global conflicts, environmental crises, and geopolitical tensions are driving significant population movements, reshaping nations and their societal structures. In this context, the research takes on a crucial role in untangling the complex web of consequences arising from involuntary displacement and its interactions with the host communities, delving deep into the developmental effects of refugee flows and the impacts on both refugees and the communities that receive them.