Our previous post on informal entrepreneurship in Alexandra focused on the typical challenges encountered by mainly informal entrepreneurs and microbusiness owners. This second post will focus on the supporting entrepreneurial ecosystem: Who are the key role players, and what kind of support is available to a typical entrepreneur in Alex? Does this ecosystem provide what is needed, and what is the actual experience of entrepreneurs in navigating this ecosystem?

On the face of it, anyone trying to run and start a small business in an environment such as Alexandra is confronted by rather daunting barriers, as explained in our article about the key challenges of enterpreneurs in informal markets in Alexandra. And yet despite the odds, hundreds of small businesses operate on the streets of the township: Sidewalk retailers, hair salons, street food vendors and restaurants, internet cafes and printing services, car cleaning businesses, bakeries and butchers. The variety itself is a reflection of the everyday needs of Alexandra’s estimated population of 300,000 people.

While this picture may seem encouraging, the reality is that many if not most SMMEs operating in Alex need much more efficient and tailored financial and non-financial support. Consider the example of Mrs Maureen Malesa. A mother of 3, Mrs Malesa is well known in her neighbourhood for her exceptional baking skills, especially her delicious muffins, cookies and scones, that she started baking in her house oven in the late 2000s. With a little start-up capital from a severance package in 2010, she invested in two commercial ovens which were installed in her small house in 7th street. Today, she produces around 1,700 scones a month, realising a turnover of around R 40,000 per month.

“I pretty much live hand to mouth”, she explains.

Mrs Malesa, Entrepreneur

Entrepreneurs like Mrs Malesa need tangible, practical support to keep going, to grow and to create more jobs. Access to affordable credit is one aspect of that, but non-financial support, such as help with registration and basic business tools such as record-keeping and cost management, can be equally important. Her challenges demonstrate some of the key issues highlighted in an impact assessment undertaken by project teams of the Wheeler Institute and Reciprocity. This research was based on qualitative data collected over the last 9 years through programmes delivered by the London Business School and Reciprocity. Key findings identified that micro-businesses operating in Alex typically need the following range of financial and non-financial support:

- Small levels of capital investment to fund working capital, stock management and infrastructure improvements, typically ranging between 1,000 and 20,000 rands. While not all micro-entrepreneurs need loans, small amounts can make a very significant difference, allowing business owners to purchase stock and buy equipment, which in turn can increase sales.

- Non-financial support, such as basic training on record-keeping, financial management and marketing (product, price, promotion, place and people)

- Premises from which to trade or operate

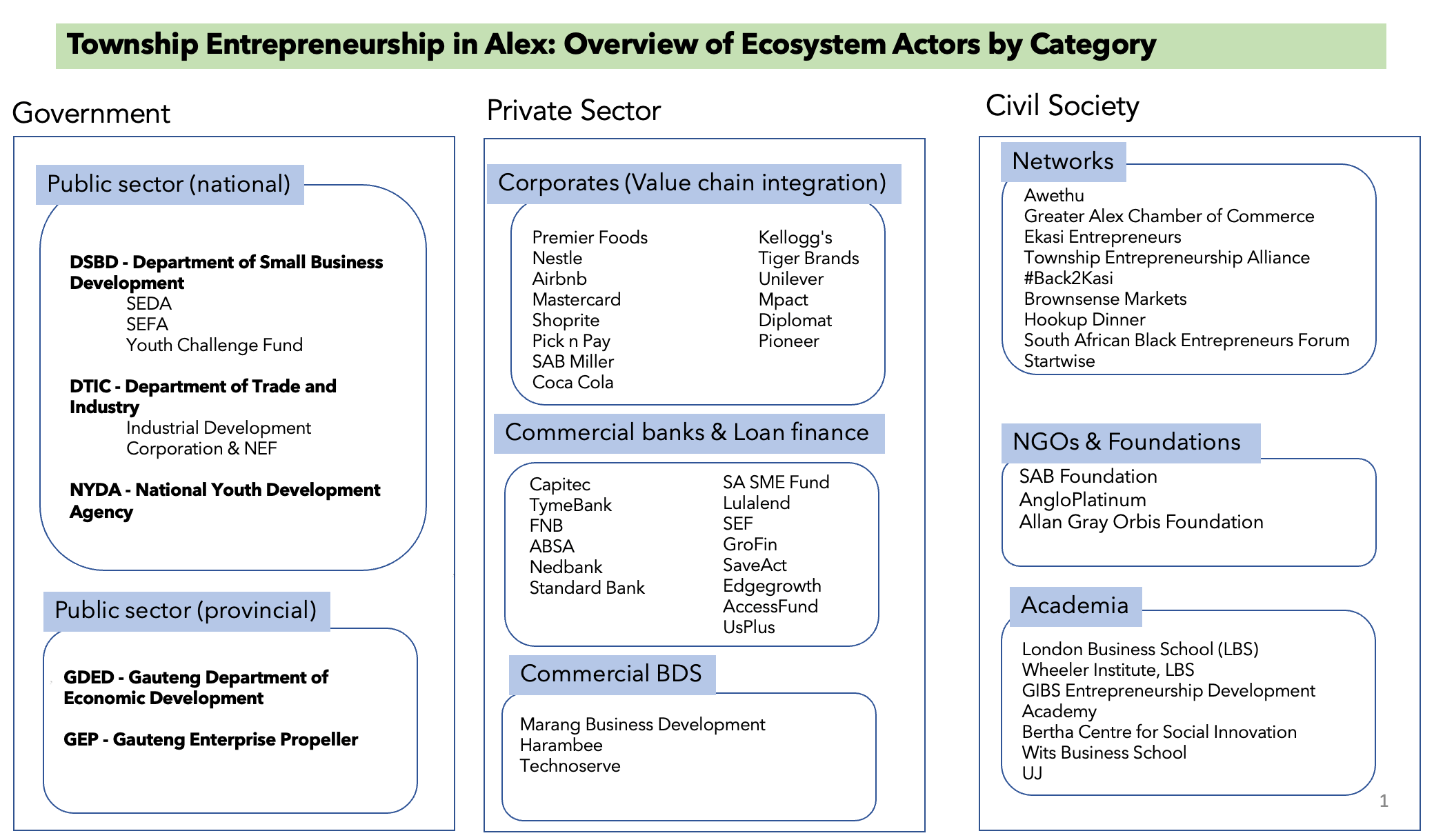

The good news is that the entrepreneurial support ecosystem around Alex is diverse and dense. Indeed, a wide range of public sector, private sector, and civil society organisations offer a mix of financial and non-financial support aimed at developing the entrepreneurial fabric, as can be seen in the chart below.

Arguably the most relevant organisations in the context of Alex are the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA), the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA), both of which fall under the National Department of Small Business Development, and the Gauteng Enterprise Propeller (GEP), a provincial agency:

- SEDA offers a range of non-financial support services, including registration and business training programmes.

- SEFA provides a range of blended finance and grant finance, including through a scheme called the Township and Rural Enterprise Programme (TREP), which was launched in 2020.

- GEP provides a range of financial and non-financial support programmes to small businesses, which include schemes specifically aimed at

In theory, Mrs Malesa could probably make good use of some of the programmes offered by the above entities, but in practice, a number of obstacles stand in the way, including:

- Low level of practical accessibility: Most of the support actors, including government agencies mandated to assist township entrepreneurs, like the Small Enterprises Financing Agency SEFA, or the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) don’t have physical offices in Alex. Reaching these organisations in person is costly and time-consuming. For example, SEFA’s nearest office is in Parktown, a wealthy suburb of Johannesburg that is geographically a 25-minute drive away from Alex, but may as well be a universe away from the realities of the township. This physical and psychological distance is not conducive to the understanding of the daily realities of doing business in a township.

- A difficult and intimidating vetting process: Most township businesses such as Mrs Malesa’s bakery are informal and tend not to meet some of the basic requirements to gain access to support, such as being registered (for example, a condition for accessing any of SEFA’s programmes), or the ability to produce a detailed business plan. In practice, many entrepreneurs find themselves downloading generic business plans at great cost that bear little relation to their own reality.

- Lack of alignment between actual needs and existing offering: As mentioned earlier, research by project teams from LBS and Reciprocity shows that basic needs of entrepreneurs in Alex are relatively simple: Small capital loans or grants, combined with basic business development services around record keeping, financial management and marketing. The TREP programme seems to address some of those basic needs, but would need to be available at a much bigger scale than is currently available.

“My clients typically struggle to navigate the ecosystem” explains Piki Phasha, a young Alex resident who recently launched Leborogo, a consultancy that provides local entrepreneurs with practical advice on where and how to get support. “First, you need to understand who is out there, what they do, and where to go. None of these are easy tasks, especially when data and transport are so expensive. Then you have to jump through all the hoops and the vetting processes. Even just registering a business can involve hours of standing in long lines and filling up paperwork. And once you get in front of the queue, you’re often treated with scepticism or worse. This type of experience is very intimidating and discouraging for most entrepreneurs in the township”.

If the disconnect between the offering in the ecosystem and the needs of business owners like Mrs Malesa can be better bridged, how much economic growth could be unlocked? How many jobs could be created and secured? Our next and final post in this series will explore this question and offer some thoughts on how entrepreneurs like Mrs Malesa could be better supported at a granular level to bridge the gap, but also what the public and private sector actors could do better.

LBS students have been collaborating with micro-entrepreneurs in Alexandra Township (‘Alex’) in Johannesburg for ten years, with over 700 MBA students helping 150 entrepreneurs respond to business challenges. This engagement with the Alex business ecosystem is delivered through a partnership with Nicolas Pascarel and Pierre Coetzer of Reciprocity, and Piki Phasha from Leborogo. Members of the Wheeler Institute were involved in establishing and delivering this engagement (Global Experience). The Wheeler Institute also collaborates with Reciprocity on identifying and implementing ways to best support the development of a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Reciprocity is a Cape Town and Tunis based consultancy looking to unlock the potential of business as an agent of economic transformation, and maximize the positive socioeconomic footprint of business in low income segments.

Pierre Coetzer and Nicolas Pascarel are the founding associates of Reciprocity.